By Professor Richard Griffiths

In January I was showing my friend and colleague Sarah Ward the sights, including a visit to the Kunstmuseum Den Haag (The Hague Art Museum). Sarah is editing a book on China’s cultural influence along the (ancient) maritime silk road. If you visit the museum, you cannot miss the fact that it boasts an exhibition on the ‘The Miracle of Delft Blue’. “Who is writing that chapter?” I asked. The reply that she did not (yet) have a chapter on the subject, launched me on a wonderful journey of investigation and discovery. She has that chapter now.

Let’s start with a few basics. First China’s blue and white export porcelain influenced blue and white ceramics everywhere. They are also blue and white. Second, for the Dutch, the experience with Chinese porcelain started in 1602, with the capture Chinese cargoes on board Portuguese vessels. It intensified after 1629 when the VOC (Dutch East India Company) established its own trade links with Chinese suppliers. And it ended in 1643 when civil war in China brought the trade to a forty-year-halt. Third, although the Dutch industry became almost exclusively identified with the city of Delft, it certainly did not start there. Delft began to penetrate the market only after the 1650s with an influx of producers from neighbouring cities. Finally, although Chinese patterns were initially imitated, before long the blue and white medium became an inspiration for innovation in both decoration and form.

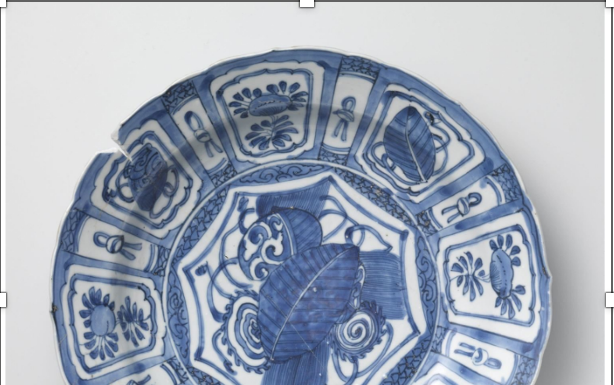

The original Chinese export porcelain plates were Buddhist-inspired and typically had a flower, bird or insect in the main design and a rim divided into panels. We will stay with plates since they allow an easy comparison of different styles.

However, the Dutch appetite for such designs soon waned, the prices they could commend fell and the VOC demanded new, more exotic designs – ‘Chinese figures, water, landscapes, pleasure houses…. with their boats, birds and animals (as) all this is well-liked in Europe.’ Since trade was disrupted before this could take effect, Dutch potters started making them themselves.

Chinese porcelain did not arrive in a vacuum. Since the mid-16th century Dutch potters had been inspired by colourful ‘majolica’ ceramics whose colours and patterns had been introduced by Middle Eastern and Italian producers. It was not difficult to copy these designs into the new blue and white colour of Chinese imports.

Another source of inspiration for the development of Dutch blue porcelain was the artistic milieu in the country itself. This was the ‘Golden Age’ of Dutch art which stretched from paintings to engravings and ceramics. The interrelationship was personal as well as intellectual since potters, engravers, glass makers, tapestry weavers, faiencers, booksellers, sculptors as well as painters were all members of the Guild of Saint Luke. If we look at Delft in the 1650s, ‘artist painters’, like and Jan Vermeer, made up only half of the 109-membership. Copies from engravings were exceedingly popular. The one below is a copy of an engraving of an Old Testament scene of an angel stopping Abraham from killing his own son. Note, however, the Dutch city-scape on the right which was certainly not in the original!

By the start of the last quarter of the century, Delft potteries alone had the capacity to produce nine million pieces annually. Even half of that figure would have been considerable, bearing in mind that the size of the population was little more than two million. The industry was known for the technical excellence of its products dominated the Dutch domestic market and was expanding rapidly abroad. There was one final dramatic flourish to come.

Between 1650 and 1672 the Dutch Republic had decided to dispense with a ruling position of the ‘Stadshouder’. When Prince William III was restored to the position, he decided that his status needed some ‘grandeur’ to match that of fellow rulers (not least Louis XIV of France). In 1684 he hired a French architect to create a baroque effect with tapestries, mirrors and grand display cabinets of the very best Dutch blue ceramics. When, through marriage, he also became King of England, he had even more royal palaces to transform. ‘Royal Delft’ flourished as never before.

An illustration of a plate could not do this period justice. The grandest piece of all, that was replicated time and again, was the so-called ‘flower pyramid’ to display individual blooms. There are several elements in their design. First, and most obvious, the blue and white colour scheme owed its origins to the Chinese porcelain imported at the start of the century. Second, the concept of perforated flower vases came from Turkey (also the source of the tulips that provoked the tulipmania of the 1630s). Finally, the idea of a tower made of porcelain may have had some roots in the 80-metre high porcelain tower of Nanjing, built in 1412 and illustrated in the Netherlands for the first time in 1665. That tower, like the towers illustrated, also had nine stories, and nine was the number associated with imperial status in China.

‘Delft blue’ is so associated with the Netherlands that it has almost become a cliché. But next time you see an imitation in a tourist shop window, why not take it as a reminder to see some of the ‘real thing’.

Places to visit:

- Kunstmuseum Den Haag

- Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (Room 2.2 and special collections 0.7 and 0.10)

- Royal Delft Museum

- Museum Princenhof, Delft