By Richard T. Griffiths

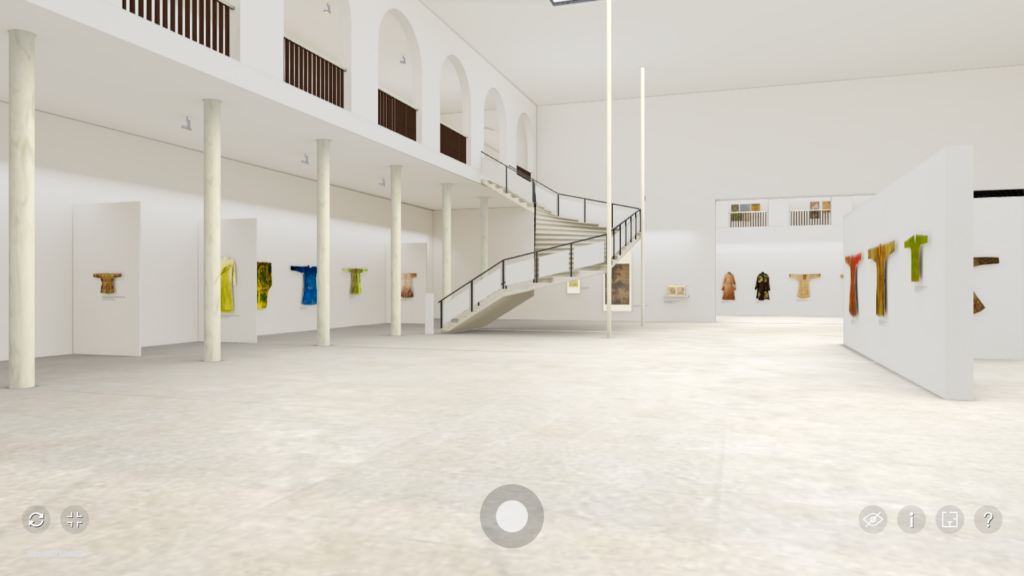

At the end of 2023, the Silk Road Virtual Museum opened a new museum site devoted to ‘Silk along the Silk Road, 500-1500CE’. It was the largest museum we have ever opened, and we had to double the floor space to accommodate all the exhibits.

It includes silk robes and motifs covering almost one thousand years of silk production in China, Central Asia, and Europe. Many of the artifacts are not even on display in the museums where they are housed. This short essay introduces you to the collection.

Sometime, over eight thousand years ago, people living in the territory of what is now China learned how to spin and weave silk. About two thousand years ago, they began to trade silk with their neighbours to the West. But fifteen hundred years ago, they lost that monopoly as the secrets, and the means of production, were lost to the peoples of Central Asia.

In both these origin stories, the humble silk worm plays a central role. The tale is told of how, those several millennia past, the young Empress Leizu was drinking tree in her garden when a silk worm fell into her cup. Upon trying to retrieve it, she noticed a thin silk thread unravelling from the cocoon. Having a wild imagination and a flair for innovation, the young fourteen-year-old gathered more cocoons and started to weave the silk into cloth.

In the sixth century CE, it has been suggested that two diplomats/hangers-on smuggled silk worms out of China by hiding them in their walking canes, thereby establishing the industry in Central Asia. This, however, is only part of the story. Silk worms only eat mulberry leaves. A silk worm, weighing two grams, would consume one hundred kilogrammes of mulberry leaves over the two weeks of its gestation, or around twenty-thousand mulberry leaves – and that is for only one single worm.

There is a second complication. In the warm wet climate of China white mulberry bushes flourish, but they cannot survive in the harsh, dry climates of Central Asia. This need not be a problem, since the leaves of the black mulberry bush appeal equally to silk worm’s appetite. However, they take twenty years to reach full maturity and start producing sufficient leaves. Either the citizens of these dry climes were already addicted to mulberries, or else the establishment of the industry must have taken considerable capital and risk.

Although China no longer had a monopoly on silk production, the actual production of silk was influenced by foreign designs and foreign methods. The silk road was not only a vehicle for the transmission of religions and cultures, consumers could experience, and buy, different designs.

Sassanian portrayals of winged animals, floral patterns, and intricate geometric designs found an echo in Tang silk production. Some Tang dynasty textiles even featured foreign scripts and characters from Persian and Sogdian languages. In the other direction, Chinese dragon motifs and flowers such as lotus and peonies influenced output in Central Asia. Central Asia and Islamic designs also exerted their influence on the later European industry.

One thing that struck me when researching for the museum was the sheer advanced state of technology. In Lancashire, at least, school child learned that in 1733 a weaver called John Key invented the ‘flying shuttle’ and that this initiated the industrial revolution in cotton. It weaves cotton thread at twice the earlier speeds. Here it is (above) all 1.65 metres tall.

I was in awe when I first learnt about it so many years ago and, as a professor in economic history, it featured in all my first-year lectures. However, nothing prepared me for my first confrontation with a brocade loom on my visit to Nanjing last year – the Brocade Museum had a dozen, and yes, there is someone sitting half way up. It, or more accurately its forerunner, was responsible for most of the complex designs in costumes on view in the Virtual Museum.

Apart from its size and complexity, what is more amazing is that it was already operational at least five hundred years before John Key changed the humble hand-loom in use in the cottage industry throughout Europe.

The origins of the draw-loom, but the earliest record of their existence lies in China and dates originally from the twelfth century CE when Lou Shu wrote ‘Pictures of Tilling and Weaving’.

In it he illustrates the processes in both, accompanied by short poems. The hand-scroll copy in the National Museum of Asian Art (Washington DC) and used in our virtual museum dates from the 13th century. The image of the draw-loom bears a striking resemblance to the ones on display in Nanjing.

A perhaps more surprising feature of the scroll is that of the twenty-four images, half of the images describe the keen attention paid to harvesting, feeding, and caring for the cocoons, and only half on the processes of spinning, waving and folding the cloth.

This makes the origin story of the spread of silk production into Central Asia, from a few silk worms hidden in walking canes even less credible. But the knowledge did spread and the resulting display of colours and patterns is breathtaking.

The robes and motifs come from forty-four museums, spread across over nineteen countries. In addition, the exhibition draws from works held in private collections.

The ‘Silk along the Silk Road’ exhibition is open 24/7. There is no need to travel and it is completely free. You can visit the museum here:

https://silkalongthesilkroad500-1500ce.v21artspace.com/

Enjoy your visit.