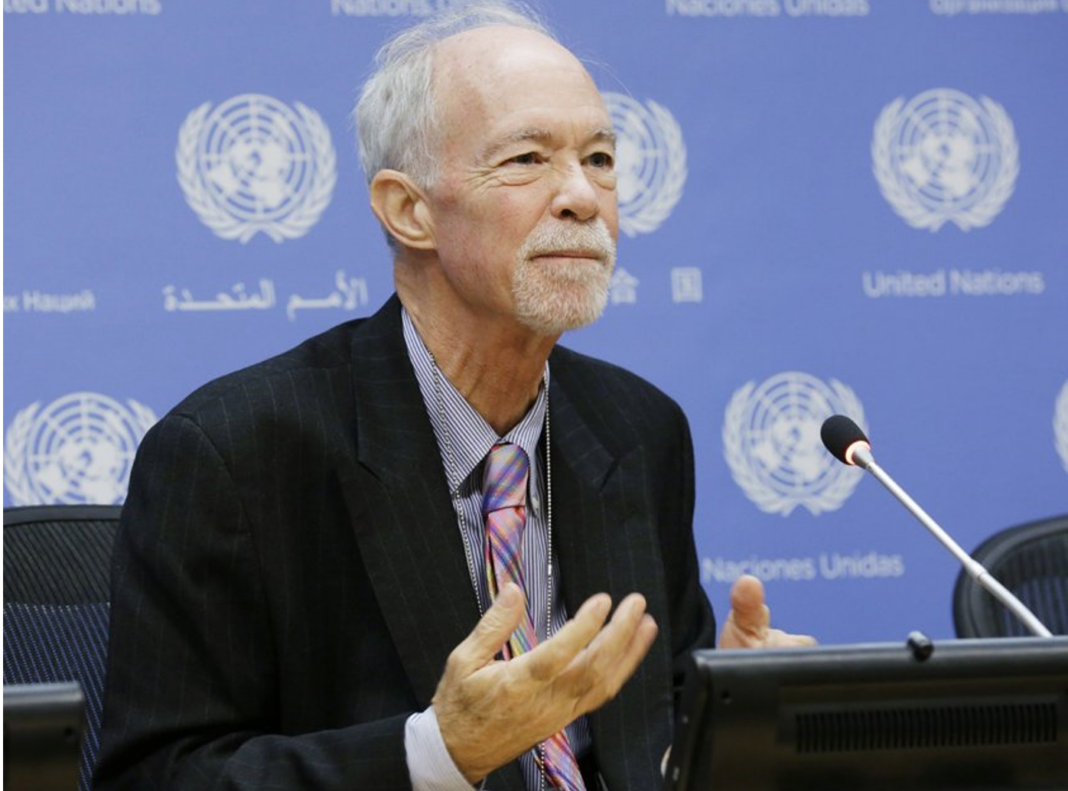

In a vibrant city of Istanbul, the Future Leaders Executive Program (FLEP) in its June segment welcomed a distinguished guest, one of the most successful high ranking officials of the United Nations in decades: H.E. David M. Malone, Rector of the Tokyo-based UN University and its Undersecretary General (2013-23). With a profound understanding of the system, global challenges and actions to address them, the distinguished guest mesmerised its audience in a thorough debate.

Talks about international development permeate current debates in academic and policy circles around the world. Yet, decades after its endorsement as one of the international community’s top priorities, the term continues to elude clear and univocal definitions, and it remains a contested concept. Dr. David M. Malone – a top Canadian diplomat – talked about his own take on the historical evolution of international development in an exchange with the FLEP fellows.

Drawing from his profoundly rich professional and personal journey, Dr. Malone noted that the concept of international development has emerged only fairly recently as a major issue on the world stage. The League of Nations, for instance, was not concerned with development, and even the United Nations did not initially devote much attention to this concept. Similarly, development was not on the agenda of the economic institutions established at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference – notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose aim was to ensure monetary stability, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, the World Bank’s predecessor), whose focus was on the post-war reconstruction effort.

How did it happen, then, that these institutions gradually took the lead in promoting and sustaining development worldwide? The key factor underpinning this shift – In Dr. Malone brief but comprehensive account – is the process of decolonization, which started in the late 1940s with the independence of India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Having freed themselves from the exploitative rule of colonial powers, these countries first sought to launch their first development programs, which often had a focus on agricultural development and famine prevention. At the time, international support to such efforts was very limited, consisting only of some experimental activities on specific technical issues, but with extremely tight budgets.

Yet, things started to change as a “huge decolonization wave” took off in the late 1950s, creating almost 80 new countries in the span of little more than 15 years. As these countries entered the UN en masse, they soon gained a majority in the organization. Questioning the UN’s single-handed focus on political and security issues, these countries – which were then labelled as “developing countries” – started to advocate for their own interest: the promotion of development throughout the developing world, with support from the international community.

These calls were rather successful. Entities such as the IBRD/World Bank, on a good track to completing their post-war reconstruction mission, soon started to shift their attention towards the developing world, ramping up the scale of their previously meagre technical endeavours. Even more importantly, international support for developmental efforts started to materialize, both through bilateral agreements between countries and in the form of borrowed funds.

While the calls for international support were successful in raising the attention and the funds devoted to the topic of development, the early developmental endeavours were not always as successful. In a number of instances, the lack of adequate infrastructure prevented these endeavours from yielding the expected results, leading leaders to re-think their focus on what – reflecting on his own choices and moral convictions – Dr. Malone termed “wildcat industrialization”. Further on, in their efforts to finance development (and, at times, to amass personal wealth in the pockets of national elites), developing countries piled up an increasingly serious amount of debt, resulting in the debt crisis of the early 1980s.

The reaction of the industrialized world was mixed. Initially, shock and surprise prevailed, coupled with calls for developing countries to repay their debt at any cost. International institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF asked indebted countries to tighten their belt to free up funds for debt repayment. Lacking alternatives, many countries did so; yet, this came at a serious price over the medium to long term. Over time, however, a more realistic outlook on the issue emerged. Creditors organized in two groups – the “Paris Club” for official donors, and the “London Club” for private creditors – and discussed their response. Eventually, the strategy was two-fold: part of the debt was rescheduled, while another part was outright cancelled.

Over the following decades, this major debt-management operation did yield important results – Dr. Malone stressed. By 1995, developing countries were fully out of the debt crisis, and government officials in industrialized countries were less worried about the overall situation. Still, tensions between developed and developing countries persisted, including at the UN. The latter asked the former to contribute to their development as a reparation of past damages under colonialism, while the former accused the latter of mismanagement and claimed full control over the use of their own funds. As of the mid-1990s, this debate had not led anywhere: everyone wanted to move on, and so they did.

The game changer emerged around the turn of the new millennium, when the UN – under the lead of Secretary General Kofi Annan – heavily invested in the creation and promotion of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The goals were narrow but ambitious; and yet, despite this ambition, most (although not all) of them were met by 2015. According to Dr. Malone, this success was made possible by the high growth rates enjoyed by developing countries through the first 15 years of the new millennium – a growth that, among other factors, was enabled by the previous debt-management strategy and by the increasing flow of international capital to the developing world.

The success in achieving the MDGs thus triggered a new process at the UN, which raised the bar and set for the world even more ambitious goals – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These objectives were underpinned by an assumption that the high rates of growth that had characterized the first decade of the new millennium would continue. As it became clear, however, this assumption was overly optimistic. The 2008 global financial crisis significantly slowed down growth, both in the industrialized world and (albeit to a lesser extent) in developing countries. As a result, international development efforts faced – and still face – increasing challenges. To respond to these challenges, the 2015 Addis Ababa Action plan sought to adopt a more sophisticated strategy to ensure funding for international development efforts. Moving away from a single-handed focus on official development assistance, the plan stressed the importance of multiple funding streams, including remittances and lending instruments. Yet, significant challenges remain as of today, and the path of international development remains uphill.

Looking towards the future, the needs of developing countries will likely be much more compelling that those of their industrialized counterparts. In short, international cooperation and developmental efforts have achieved a lot over the past 78 years, but much more has yet to be achieved. As we enter the new-realities era, the world should be aware of that.

As the event draw to a close, H.E. David Malone and President of ICYF, Taha AYHAN (as a principal host to the event) both expressed what all participants had already concluded throughout the talk: that the Future Leaders Executive Program offers a unique setting and the winning narrative. Excellency Malone and President Taha accorded that this particular format – in which an established experience meets the new passions, drives, rhythms and colours through cross generational leaders’ talks – represents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for emerging leaders from verities of environments: the state, intergovernmental, and corporate sectors of all meridians.

The mesmerising FLEP-flagship of insights and wisdom, passion and vison gets a full swing sail once again in the Fall of 2023.