By Prof. Richard T. Griffiths

Dunhuang is an oasis town at the edge of the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Its waters have welcomed travellers over the centuries. I was privileged to be there in 2017. Nearby are the Mogao caves, with their Buddhist images and decoration.

They are also famous for the thousands of documents discovered there, and stolen/saved by the Western archaeologists, which shed new light on the culture, beliefs, and daily life between 1500 and 1000 years ago.

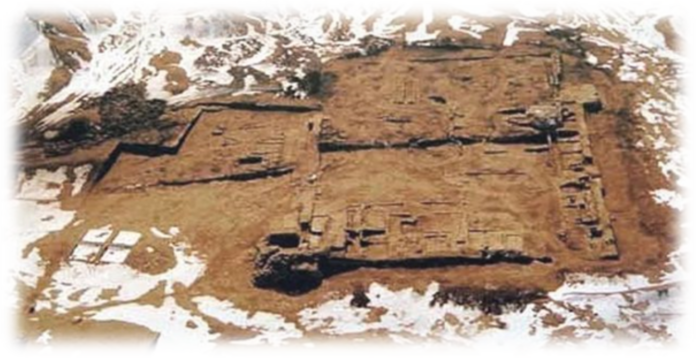

In September 1987 a maintenance crew, working on a road some 64 kms east of Dunhuang, stumbled across an area of grey coloured sand indicating the existence of some ancient building.

The chief archaeologist went in person to investigate. It cost him a whole day simply to locate the site, but on the second he and his team found some pottery and some silk that allowing them to place the site in the Western Han Dynasty (202BCE-220CE). What they had discovered was one of the 80 postal stations between Chang’an (the capital of Han dynasty China) and Dunhuang, one almost every 20 kilometers.

It was important discovery – no more, no less. However, when two years later, evidence emerged that the site was becoming prey to looters, the authorities authorised an emergency rescue excavation. The excavations lasted until 1992 and it took another three years to register all the finds.

A total of more than 70,000 pieces of various cultural relics were unearthed, including 30,000 pieces of pottery, 6000 pieces of wool, pieces of metal tools, remnants of food and the bones of various animals.

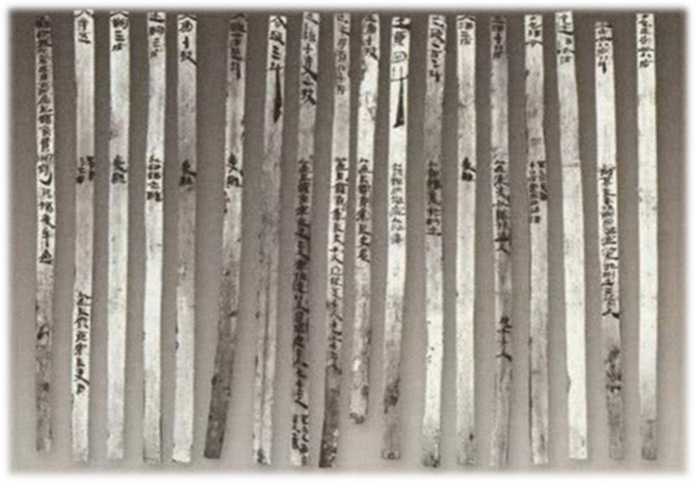

Most important of all, they discovered more than 23,000 Chinese bamboo slips with Chinese characters, 10 silk books, 10 paper documents, and more than 460 pieces of linen paper. It is these that allow us to reconstruct daily life of an outpost at the edge of the empire.

The written slips of bamboo tell us how this the site acquired its name. Legend had it that a general provided water for his thirsty troops be striking a rock with his sabre allowing water to flow. Its source was four miles up a ravine to the north of the pavilion. The spring was rumoured to be magical, adjusting its flow according to the number of people needing it. The name ‘pavilion’ changed over time…. from pavilion, to shelter, to post-station, to relay-station. Its functions remained the same – facilitating the movement of correspondence, receiving official delegations, and providing food and accommodation for travellers.

The site itself was a based on a 50×50-meter square courtyard with high walls (to protect from the high winds) and 29 earthen houses of various sizes inside and outside the courtyard. There were also some auxiliary buildings such as stables on the south and east sides of the courtyard. Moreover, a one-kilometre section of the post road, four metres wide, was discovered near the north wall.

The bamboo slips provide the insights into daily life at the edge of the empire. This was not easy since they were mostly written in a script that has long since disappeared. This turned out to be a kind of simplified-Chinese developed by the military as a form of shorthand for writing messages quickly. The most complete document comprised 18 slips.

It also captures one of the main functions – receiving official delegations. It is early spring and the weather is cold. Se Fuhing, the chief officer of the station learns that a delegation of 84 officials and 300 soldiers belonging to Changluo Hou Changhui, a high ranking courtier, was due to pass by. Knowing the imperial hierarchy, Se Fuhing decides to pull out all the stops and preside over a feast for his guests – there are more than ten kinds of food on the table: beef, sheep, chicken, fish, wine, rice, millet, sauce, black beans and soup.

Kings and queens, ambassadors and envoys, from over 20 countries are recorded as having passed through the Hanging Spring’s facilities. In one reception, the King of Khotan arrived with 1,060 followers and more than 300 cups were used (everyone got to eat, only the more distinguished guests got to drink).

The passage of Princess Winsum required the laying of a special carpet in the dining room. On and on go the records – delegations of 34, 35, 70, 300, and even bigger passed through the site (those not qualified for a room slept in tents in the courtyard). In many cases, the accompanying cattle, camels and horses were also recorded – these would be part of ‘tribute trade’ which was really a form of high-stakes barter trade. There is one thing that is missing from all of this – there are no records of caravans passing through and in all the documentation, only 20 slips have any mention of trade goods. This should not be taken to mean that there was no trade. Many of the slips record along-side the ‘tribute’ animals, the presence of ‘private’ horses and camels. Clearly private merchants were travelling with the delegations, or even masquerading as official delegations.

On the wall of one of the outer buildings, archaeologists found the inscription of an Imperial edict dating from 5CE – entitled The Monthly Ordinances for the Four Seasons. There are 50 monthly orders that specify what should be done and what should not be done each month. The orders establish that all work involving agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, logging and fishing should follow the natural time sequence, in effect trying to protect the agricultural ecosystem, forest resources, animal and water resources… possibly the world’s earliest “Environmental Protection Law”.

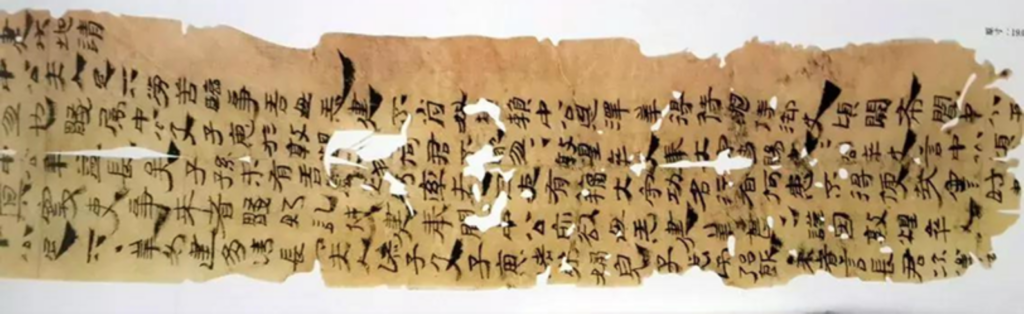

Finally, I must mention one personal letter, written on silk and beautifully preserved. It is written by Yuan, a junior officer, to his friend and colleague, Zifang. After the usual greetings, there follows a list of suggestions and requests – buy yourself some new leather shoes and five good quality brushes, don’t forget to visit Jing Zifang, remind the family to write, to get a private seal engraved for Lu An, and buy Gua Yingwie a whip. I wonder if this was his own copy and whether the original was even posted. Did Guo Yingwei ever get his whip?

The site has now been backfilled to protect its integrity. Visitors can see the outlines and the corner piers on the north east and southwest. Meanwhile, there are tens of other post- and relay stations waiting to be discovered. Time will tell what treasures they will reveal. The Hanging Spring Pavilion is one of the ten sites featured in an exhibition about the Caravanserai of the silk road.

You can find the exhibition and the supporting eLibrary at:

https://silkroadvirtualmuseum.com/caravanserai