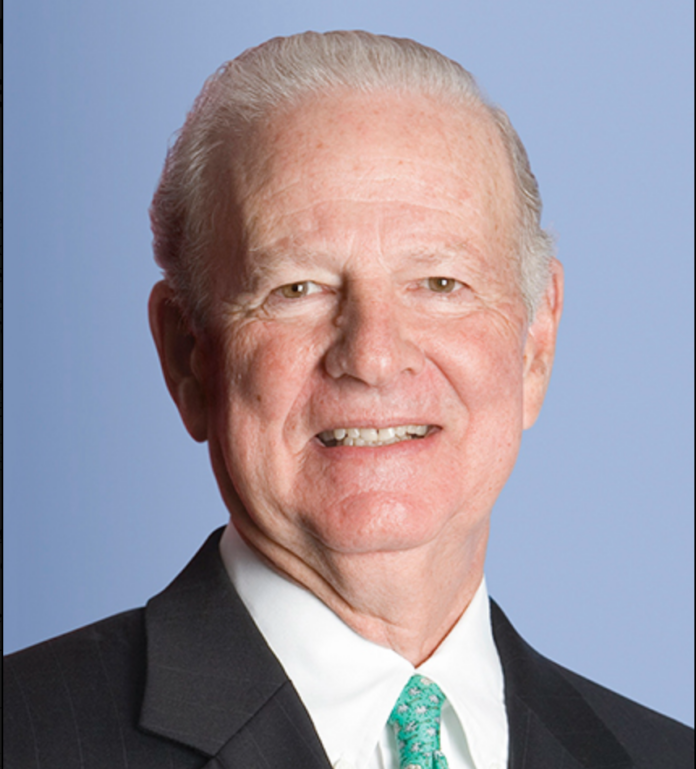

07.07.2023 (Published by Caucasian Journal) Today we are especially honored to meet with H.E. Tedo Japaridzze – one of the most experienced Georgian diplomats, former National Security Adviser and the Secretary of National Security Council, Minister of Foreign Affairs and chairman of the parliamentary Committee for Foreign Affairs.

Mr. Japaridze also served as ambassador of Georgia to the United States, Canada and Mexico, and was secretary-general of the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC).

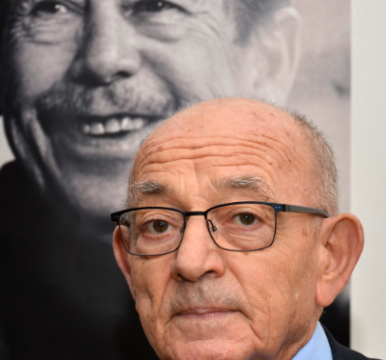

Alexander Kaffka, editor-in-chief of Caucasian Journal: Your Excellency, welcome to Caucasian Journal. There are so many things to talk about, that I would rather leave it up to you what to pick from the today’s ample “menu”. Let’s perhaps start with your perception and state of mind: How would you summarize what you feel about the current moment – as a person, a citizen of your country?

Tedo Japaridze: I am, indeed, very much grateful that you invited me to talk. Since the early 1990s after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and whatever was left after that colossal disruption, we have been discussing tortuously our mutual perspectives as the collapse of the USSR was so traumatic for all of us – to this day, it continues to define not only Russia’s identity and its geopolitical imperatives but also of its immediate neighbors and far beyond, and naturally, of Georgia as well. Since that period, the entire world, including the post-Soviet space, has changed, turning from a no man’s land to something else, however, maybe still unclear to us. From a frightening stability of the “Cold War” up to the stages of “post-Soviet,” “post-modern,” “new normal,” “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns” and many others, not well-defined and precise interpretations and rationale, especially of mental maps and landscapes, delusional ideas, predominantly, in tragic forms, and the brutal war in Ukraine reaffirms that distressing fact on the ground.

Plus, if we add to that quagmire the worldwide pandemic (which we all experienced and, I would say, unevenly survived) had a calamitous and misbalancing effect on entire global affairs. As for our part of the world, the South Caucasus, the Second Karabakh War has drastically altered the strategic landscape of our wider region. And that global paradigm shift keeps moving at pace. I recently came across Professor Paul Stephan’s (an old-time friend of mine from the Virginia University Law School) latest book, “The World Crisis and International Law,” from which an excerpt seems to stand out: “We live in a dark time. Not so long ago we thought a new dawn broke when the Cold War ended, bringing universal peace, general prosperity, worldwide connectivity, human rights, and the international rule of law. Instead, disillusion has overtaken us in the wake of shocks and abounding threats. We face uncivil politics, economic anxiety, and tribal conflict throughout the rich world. Authoritarian nationalists seem the coming thing around the world, rich and poor alike. Peace and prosperity do not. Many believers in the liberal international order now feel, like Marxists in the 1980s, that history has turned against them.”

Please forgive this long quote. We all indeed exist – and need to coexist – in dark times as nationalist and authoritarian forces are animated not only in Europe and the United States, but also in the post-Soviet space, including my own country, Georgia.

We usually have our choice between bad and worse, and for Georgia that survival pattern always has been about how to preserve our identify, but at the same time to take care of all security implications, and how to find out realistic balances between them.

What will be the philosophical and moral fixings for the construction of our region anew and specifically of Georgia in the near future to be tuned-in properly to those seismic changes around? Why did I pose that question to myself? I have been curious about this for a long time in grand strategic chunks, especially after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. So, should we be rethinking the history of decolonization to include Russia? Is Ukraine for Russia comparable to the experience of Suez for the UK and France? Are there other comparable examples in our history? Where are we all drifting off to? How should countries like Georgia survive those “interesting times” (as the Chinese curse has it, wishing their enemies to experience “interesting times”) and how to harmonize to those new strategic arrangements of world politics unfolding around us? So, you see that instead of answers, I have posed even more questions.

As Professor Neil MacFarlane, another good friend of mine from Oxford University, loves to say whenever we discuss the future perspectives of global affairs, including, naturally, of Georgia (and Neil and have been doing that since 1990s!): “THE FUTURE IS A DIFFERENT COUNTRY, Tedo!” Indeed!!! Nobody has ever been there, have they? Professor MacFarlane is right. However, that does not mean that we should not think about the future perspectives! However, to proceed that way, we, Georgians, should be extremely rational, pragmatic and realistic, as we live in a rough neighborhood and in a generally a ruthless world, where vibrant developments happen and those things predominantly are bad. So, we, Georgians, usually – and historically, due our geography and different strategic factors – have our choice between bad and worse, and for Georgia, that survival pattern always has been about preservation of our identify, but at the same time taking care of all security implications, internal and external, and finding out realistic, accurate balances between these challenges.

It’s not easy, believe me, as other global or regional actors, especially Russia, have different visions on those problems and interpret everything only in their own way and according to their own interests, beginning from security, stability, economic cooperation and through independence and sovereignty, particularly regarding their immediate neighbors. Why? In the case of Russia, the purpose is to dominate and control its periphery and keep neighbors unstable and relatively unsettled, according to so-called pattern of “negative conditionality” – either with us or against us, thus promoting, as Russian policy-makers think, their strategic interests. I had so many polemical but futile, ineffective discussions with my Russian colleagues, including, by the way, Russian democrats and liberals.

AK: Even before the current unprecedented political and military situation in Europe, Georgia and many other countries had been living though very turbulent times, with crisis, pandemics, and other factors of instability. And the challenges the world is facing now are plainly unprecedented and unthinkable. Given your vast political experience, how would you characterize the today’s situation on a global level? Can you name three top priorities for the political leaders to cope with?

I would humbly advise Georgia to be predictable, rational, pragmatic, trustworthy, useful and valuable for partners and immediate neighbors; be an “institutionalized democracy” based on the rule of law.

TJ: I would agree with whatever Professor Paul Stephan outlined in the above-mentioned fragment but at the same time I am not that alarmistic. Yes, the situation is stormy and global affairs have been passing through an immensely neurotic reformatting and recalibration process. Consequently, a country like Georgia again should think resolutely and resiliently about its own identify and security and how to tackle this existential dilemma. How to find those balances and compromises but do that without conceding its strategic agenda and goals identified by citizens of Georgia and Georgia’s Constitution.

Let’s turn back briefly to that pattern of Russian “negative conditionality.” As acknowledged by Thomas Graham of Kissinger Associates (again, apologies for such a long quote!): “The war in Ukraine has changed the strategic dynamics in the former Soviet space and almost entirely to Russia’s disadvantage. Russia has lost Ukraine for at least a generation, as the conflict has strengthened Ukrainians’ sense of national identify and fortified their determination to minimize ties to Russia and anchor their future in Europe. Moldova also has a European future, and Russia will likely find it increasingly difficult to maintain its influence in Transnistria, which will be surrounded by “pro-European” territory. Turkey is already enhancing its influence in the Caucasus and will likely continue to do so at Russia’s expense. Meanwhile, Chinese influence is growing rapidly in Central Asia, where concerns about Moscow’s expansionary ambitions are growing, especially in Kazakhstan.”

Consequently, what has Russia gained? But more important to me is how should a country like Georgia survive under that impulsive circumstances and fluctuations in its immediate neighborhood? Again, not an easy question to find a proper answer to! I would humbly advise Georgians under those quivering conditions to be predictable, rational, pragmatic, trustworthy, useful and valuable to your strategic partners but also to your immediate historical neighbors who usually have long memories. Georgia itself should keep going on the democratic way, towards, as we say, an “institutionalized democracy” based on the rule of law, and do so with a supposition that democracy is a heavy burden, which our authorities and the opposition should take upon their shoulders and embark on that never-ending journey of perfection though excruciating and frequently disorderly processes.

As Winston Churchill sarcastically admitted in 1947, “democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” So, at present, we cannot afford to divide the country amongst winners and losers, if we ever could afford it. I once wrote that we need a more diffused sense of power. We cannot fail to affirm confidence in our democracy, nor should that depend only on western intervention. Our Western friends and allies may help, assist, but this is our democracy, our own project that we must build with care and diligence, accepting mediation or arbitration, but not relying on it systemically. The citizens of Georgia must never again be forced to choose between “effective” and “representative” democracy. I can reaffirm that during former Prime-Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili’s term, the country bolstered its effectiveness brand as well as its democratic aura and that was acknowledged by foreign counterparts and experts.

Education should become the fundamental element of Georgia’s advancement towards the resolution of that centuries-old dilemma: How to preserve our identity in a secure way not to damage it.

I cannot advise current world leaders, regarding their top three priorities, as you urge me to do, but were I in the shoes, for example, of current Georgian leaders (which I apparently do not want to be!), I would concentrate my efforts on education, education and, once again, education.

Education should become a fundamental element of Georgia’s advancement towards the resolution of that centuries-old dilemma I mentioned above: how to preserve our identity but do that in a secure way not to damage it. Again, easy to say but, unsurprisingly, not easy to resolve that dilemma. Education, and knowledge in general, are the essential, basic instruments: If we do not broaden and deepen our knowledge, recalibrate our awareness regarding the entire context of global processes and trends, we may as a country be lost in the tangles of global affairs.

The “knowledge economy” (and not “globalization,” which as it looks in its current format has expired its resources and potential), as identified by Professor Paul Stephan, is key to flourishing in today’s world in different areas of politics, economy, security and stability. And a knowledge economy will be crucial in winning our battle for the future. I think that Georgia and Georgians of any and all political or ideological inclinations should be focused on that strategic agenda: the future!

AK: If we look at the global political-military toolset of today, we see that the importance of the military tools is growing, while the political and especially legal instruments are losing strength. If there is indeed such a trend, what are the implications? What’s the future of global security?

TJ: I have just talked about that in my previous answer. There’s no way to succeed militarily or politically without being successful in the area of the “knowledge economy”. Just the recent example is – and let’s again quote MacFarlane and Thomas Graham. Look how Russia has been endeavoring to emulate its old imperial escapades, following a 19th century logic and using old military instruments [knowledge – TJ] but vexing to accomplish those goals in a completely different world. Isn’t it simply a new interpretation of an old aphorism I heard many times from wise people – last time it was Neil MacFarlane – that history repeats itself as a farce?

AK: Let’s switch from the global scale to this country. Georgia’s position is raising many concerns. The internal political situation is worrisome – the political life is deadlocked; it threatens the investment climate and the international image of Georgia as well. What is at the root of the problems?

I called Georgia the “Peter Pan of the Caucasus” – a lovely character, but never grown up, matured.

TJ: These are not only Georgia’s problems, by the way. But let’s try to focus specifically on Georgia and its internal problems. I mentioned the elements of institutionalized democracy – strong political institutions, the rule of law, fair elections, political and media pluralism or whatever has been formulated in those “EU 12 recommendations”. I once said that Georgia is trapped in a ‘Catch 22’ situation: The government does not regard the opposition as the future government and the opposition is not acting as a future government. We must expect better and more of each other. Was I too wishful or naïve desiring this? Was I being a typical Georgian dreamer? And of course, there should be grand strategic ideas in the country, ideas that unify the elites or political classes together with the society and move the country ahead and not predestine it run irrationally and fatefully around a vicious circle or spiral of instability, sometimes even lunacy, for years.

On one occasion, I called Georgia the “Peter Pan of the Caucasus” – a lovely character, but never grown up, matured. You know that foreigners tend to say that Georgia is not a boring country – something always happens there, either good or bad. I wish maybe as an idealist, for Georgia to become as boring as Estonia, where things happen – sometimes maybe vibrant ones – but Estonia moves resolutely ahead and earns the top levels regionally and globally. Therefore, my perhaps naïve optimism is based on an assumption that one day Georgia will turn into what we call “secure democracy” when a country stands firmly on its both feet and makes its own sovereign and independent decisions without looking left or right.

AK: Ready answers to these problems are hard to find, especially if we ask responsible professionals, who are always very careful in wording. But still, are there any steps that you may suggest?

TJ:I am not an oracle but I may only humbly advise the current Georgian politicians of any kind: The government, majority or the opposition (I know that they all hate to be advised as they assume that they know everything!) – to get rid of that obsession and greediness for power, to keeping that power for years! Again, my message is not only about those who are currently in power but also about those who want to grab that by all means and contest in that regard not only with their opponents but with themselves vis-à-vis who’s more democratic, more liberal or more “European”, “pro-US” or “pro-EU”.

I remember one Greek friend of mine described Georgia as a land of “feudal pluralism” where everybody either pretends or desires to be a king who knows – and it’s ultimately only him or her (!) – how to navigate Georgia properly to safety, as some Georgian Moses. Instead of that sort of “pluralism” Georgia needs to consolidate its political agenda and identify its top strategic priorities, which, by the way, as I said above, have been identified by the Constitution, and, by the way, quite a long time ago. That “feudal pluralism” and the “rivalry” within it could have been funny to watch had it not impacted or affected damagingly the perspectives of Georgia itself. Sometimes it seems to me that there are more “democrats” and “liberals” around these days in Georgia than there is genuine democracy or liberalism itself. Once I wrote that when maxims of Jonathan Swift and George Orwell are taken together, messed with each other, and projected on Georgia, the saddening tears alas trump an obvious laughter.

AK:As a foreign affairs professional, would you like to comment in particular on Georgia’s bilateral relations? One of highlights in your distinguished career is serving as ambassador to the Unites States. I am sure you have worked with some of the brightest political figures, and there are many interesting episodes that you might share with our readers.

TJ: Yes, I have met many legendary political figures, including prominent US, European, regional politicians and academics – Presidents, Prime-Ministers, Members of Congress, Secretaries of State, MEPs, senior diplomats, scholars, opinion-makers and shapers/influencers. With each of them, I endeavored – sometimes even struggled and unfortunately failed – to talk about Georgia as not only some “geography,” a country with its unique historical, religious or cultural legacies but also as a specific strategic context, a country possessing distinctive institutional and collective centuries-long memory dealing with its rough neighborhood, including long imperial memories and current regional perceptions, which frequently – and unfortunately – usually turn into the calamitous realities for us.

A while ago, I remember, I asked Secretary James Baker, who was already retired, why the powerful United States cared so much about Georgia’s independence, sovereignty, stability and security. His response was indeed strategic and his words are still resonating in my memory: “The United States want to have as many as possible clusters of democracy and stability throughout the world and keep those clusters as far as possible from America. We see Georgia as one of this kind of clusters. And if the US succeeds with that grandiose plan, the United States itself would be secure and stable.”

Secretary Baker articulated those views in 1997. That same year, William Courtney, US Ambassador to Georgia, delivered a message to the European business community gathered in Brussels: It was time for Georgia to cease being a problem and a headache and become an opportunity for investors, and indeed an island of stability and democracy. Undeniably, we were going that way, however, then some things, well-known to us, happened here and there and Georgia is where it is now: we do our best to move ahead, accomplish our strategic agenda, maybe sometimes zigzagging here and there, but still moving ahead relatively resiliently. And that makes me cautiously optimistic.

Back to my meetings with political dignitaries and celebrities. I had an opportunity and privilege to meet and talk not only with US, European, Asian VIPs, including Turkish, Iranian, by the way even President Vladimir Putin. These were exceptionally interesting meetings, especially with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and with high-level Iranian officials. No way to forget my strategically exceptional meetings with President Heidar Alyiev, President Suleiman Demirel, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, meetings full of vision and wisdom! By the way, I met with President Vladimir Putin a couple of times , and particularly the meeting in Bocharov Ruchei in 2002 was indeed “unforgettable” (exactly our impromptu exchange on the Georgian conflicts and the ways how to resolve them), but let’s talk about that some other time!

Among those official or unofficial encounters, I particularly remember my meeting in Prague, in March of 1993 with Luboš Dobrovský, a legendary ally and associate of Vaclav Havel, one of the heroes of the Velvet Revolution, Mr. Dobrovský by that time was the Head of Havel’s administration and, as I recall, we had a long conversation throughout which he meticulously and practically inquisitively was bombarding me with questions concerning the meaning of the notion of the “near abroad,” familiarized, if you remember, in the post–Soviet vocabulary and discourse by the Kremlin, classifying thus the former Soviet space and the world beyond it. In a while, I asked Mr. Dobrovský why he was so much pedantic about that term and he answered: “We, Europeans, should be extremely careful, aware and familiar with all details and nuances of Russia’s interpretations of that notion and how they instrumentalize them towards former Soviet republics, as what they consider today as their “near abroad”, tomorrow may turn out to be their “middle abroad” and afterwards go further.”

So, where are we all now? Where is Georgia moving to and what’s our strategic agenda and the instruments to accomplish it? I have posed those questions above and I acknowledged that I do not know the exact answers as I am now an outsider and I do not know the details and nuances of Georgia’s current political process – and those nuances and details, usually are invisible for an outsider and are essential elements of policy-making. But still those magical sentiments of Mr. Dobrovský are sturdily cemented into my memory. By the way, we talked much about my meetings with variety of foreign high-level officials, but the most memorable and honorable were my encounters with President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, President Eduard Shevardnadze (daily for many years!!!), President Michael Saakashvili, the leadership of “Georgian Dream”. Each laid a solid brick in the foundation of Georgia’s independence and preserving its sovereignty, naturally, making their mistakes and missteps on that tumultuous way. Sometimes it seems that those blunders were just unavoidable and inevitable, as we say, home-grown, but some of those “mistakes and missteps” were just imposed on Georgia from outside (in the formats of conflicts, wars, internal vibrancy) and frequently dragged Georgia into strategic stalemate, hindering its progress and prosperity.

If Georgia survived as an independent and sovereign state, preserved its stability, security, achieved successes in its uphill and never-ending democracy-capacity building, all of this occurred thanks to immeasurable support and assistance of the United States.

AK: Georgia-USA relations in a time perspective… I think it’s a very interesting case. We see such extremes as naming a Tbilisi’s street after an American president to ‘personal attacks’ on the US ambassador… How important is America to Georgian people? How do you see the future Georgia-USA relations?

TJ: Naturally, my answer to that question would be just a personal one, as already admitted above, nowadays I am not an insider of those very complex and comprehensive relations. On the other hand, I was among those Georgian leaders, politicians and diplomats who laid the first – and, I would say, very rock-hard, strategic cornerstone in the foundation of Georgia – US relations. That’s an extended, thirty+ years’ long story how that multi-strategy journey advanced. However, there’s one emotional description of those relations, which I have recalled many times and want also to share it with you: If Georgia survived as an independent and sovereign state, preserved its stability, security, achieved successes in its uphill and never-ending process of democracy/capacity-building, all that occurred thanks to immeasurable support and assistance of the United States.

Of course, this was not a linear process and Georgia confronted certain wars, conflicts, drawbacks, failures and zigzags in that tumultuous process (I talked briefly about them above), but the United States always stood firmly next to Georgia whether these were achievements or failures, ready to help and assist and navigate Georgia properly and securely. While maybe assistance packages were timid by American standards, their cumulative value was significant. Each million spent in “our part of the world” was a geopolitical commitment to all of us. In effect, the United States was sponsoring our aspirations rather than buying out our destiny. As I learned recently from Ambassador Kelly Degnan, the US has provided to Georgia more than $6 billion in assistance, as well as other kind of support. That’s a colossal amount assistance to make Georgia a functioning democracy!

I remember, in 1998 I was invited to a ceremony celebrating the first $31 million US Government assistance package to Uzbekistan. The host was Ambassador Richard Morningstar, by that time, Special Adviser to the President and the Secretary of State on Assistance to the New Independent States of the Former Soviet Union (FSU). The guest of honor was Hillary Clinton, the First Lady at the time – but much more than that in terms of her influence.

In effect, the United States was sponsoring our aspirations rather than buying out our destiny.

I was asked by Ambassador Morningstar to close the event with an impromptu speech. I started by thanking the US Government for its immeasurable assistance for former Soviet republics, later straying towards a more personal tone. I talked about my son, Nika, who since 1994 (when we arrived in the US) grew into a typical American suburban teenager and was about to sit his final exams at Bethesda High School (BCC) in Maryland. So, I added his and his generation of Georgians’ American experience to the multi-billion-dollar package of US assistance that literally laid foundation of the newly instituted independent and sovereign Georgia. And then I wondered if Nika’s generation – or any generation thereafter – would ever repay the loan the people of Georgia received from Washington or, better to say, the citizens of the United States. I wished that our country would grow into a state with the rule of law, irreversibly democratic, affluent, substantially sovereign, capable of paying back its debts. The point I made was that for Nika’s generation of Georgians, debt and our collective “loan” were not merely financial but also moral.

So, Georgia’s commitment to the United States was not measurable. Any message of America’s support was what Georgia stands for and that spreads instantly across our small country like a wild fire. Everywhere, even in the smallest villages, Georgians who have fought so hard to wrench their nation from a future of servitude and occupation onto a pathway of democratic Americans values and civil society say it. Georgia has come a long way. By all means, our deep faith and legacy have been the engine of our transformation, fueled by the courage of a small but talented population. History has rocked Georgia brutally and Georgia has been repeatedly conquered, subjugated, and colonized. Yet we have lost neither our own vision of freedom nor our organic attachment to Western civilization. We have grown stronger and more consistent in our commitment to enshrine freedom and democracy as our national destiny. Yes, we are not perfect, however, who’s perfect in that imperfect world? And, I hope, we will not be moved from this path.

Even the process of engagement (not membership!) with the EU and NATO will make Georgia a better place than it is now.

AK: Georgians identify themselves strongly with Europe and the West in general. That’s a very valuable asset, but must be handled with much care, otherwise this resource might evaporate. How do you assess the EU and NATO’s attitude to Georgia (and vice versa), and the progress of Georgia’s European integration?

TJ: As I said many times, we live in a transforming neighborhood and attempt to maintain good relations with just about everyone. Turkey is our largest trading and strategic partner. Iran is returning to the region, including to Georgia. China is a new and powerful presence; the Middle East has discovered Georgia and invests here. Azerbaijan and Ukraine are also our strategic partners and we appreciate the normalcy and good-neighborly political, trade and commercial relations with Armenia. The Black Sea is a new strategic frontier, and Georgia is prominent on that landscape, specifically on its eastern shores. We acknowledge that all around us, other states, are going through their own transitions, some better than others, which is why security was such an important part of our conversation. We hope that one day we will become part of NATO and the EU, however, we also understand (I hope) that it looks like it’s a long-term perspective. However, let’s be positive regarding that overly pessimistic “long-term” perspective”: I think that even the process of engagement (not only membership!) with the EU and NATO will make Georgia a better place than it is now.

Georgia should be more visible, active in different strategic formats and discussions. We “disappeared” from those strategic arrangements, landscapes and discourses or just marginally emerging here and there. That’s not good indeed!

Therefore, all those “12 recommendations” and NATO guidelines are about that: how to make Georgia a normal, functioning democracy as the membership both in NATO or the EU, besides institutional capacity, including the military one, are based on values, principles and democratic practice. I hope that we are realistic about how this process may unfold and thus we should be ready for the opening of any window of opportunity. On the other hand, we have learned to be patient, not to rush the tempo, even as promises are made and then delayed as if we are fixated in front of revolving doors: we are in and promptly are out! We understand that, as I admitted above, the process of engagement is only slightly less important than the destination. That said, the prospect of NATO and the EU membership are powerful motivators for Georgia’s democratic development. If we fail to make progress, hope suffers, and with diminished hope the Georgians’ enthusiasm for its democratic development will wane. But in addition to all those NATO and the EU criteria and standards, Georgia itself should be more visible, active in different strategic formats and discussions. I see that we kind of “disappeared” from those strategic arrangements, landscapes and discourses or just marginally emerging here and there. That’s not good indeed!

AK: Georgia vis-à-vis its neighbors and other post-Soviet countries, including Ukraine and Russia… Again, so many things to talk about – what would you like to emphasize? What is your strategic advice?

TJ: As I admitted many times, nowadays I am not giving strategic advice because I do not know, as I admitted above, important details and nuances of the ongoing political process, which, as I watch that from outside, is slightly neurotic, chaotic, turbulent. By all means, one needs to be smart, wise, cautious to navigate properly through those cyclonic global political developments. So, to do that properly and as accurately as possible, one needs to think strategically and contextually, calculating appropriately not only what will be good for his/her own country but also for your partners, neighbors as well and – that may sound surprising and extraordinary to some – even for one’s opponents.

You remember the famous British military dictum? “Firstly, you need to penetrate under the skin of your opponent and only after that make your own judgment and final choice!” To proceed that way would not be a simple calculation! Why? While doing that any Georgian decision-maker (or, for that matter, any decision-maker who represents a small and relatively weak country as Georgia is and plus, located in that kind of rough neighborhood) always needs to keep in his/her mind Georgia’s own strategic agenda and interests and not to concede an iota of them. A hard dilemma, doesn’t it?! To deal with that kind of impasse, it looks like any Georgian decision-maker must deal with a classic Catch-22 situation or a “lose-lose” option. So, that’s the reason why any Georgian decision-maker needs to be very cautious. But here’s a paradox: being cautious does not mean to be cowardice and overly panicky or create that kind of image and perception. Let’s pose a straight-cut forward question: who wants to engage Georgia in military activities or open the “second front” or whatever? Georgia has experienced those escapades, brutal conflicts and wars as well as some reserved reactions on them, including just “strong statements” from our Western partners. As result we have lost 20% of our territories and that makes us vigilant. But, as in our life, there are the situations when you need to take the right side, be, as people say here, in my Vera neighborhood, “on the right side of the fence”. And what’s the right side of the fence in our case? What was the choice of Georgia for centuries? Has it changed? Isn’t our choice same and again, between bad and worse? So, to be on the “right side of the fence” does not mean to be impulsively and hotheadedly against somebody or something! It means to make a moral decision, accepted by the civilized world, based on its values and principles.

Now back to your question. Russia is our neighbor and apparently, we cannot change our geography. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Georgia desired a durable and mutually advantageous relationship with Russia, which is in the common interests of Georgia and Russia, as well as in the interests of the United States and Europe. We pledged for years that we will do all within our power to develop such a relationship, as long as Georgia’s national interests are not compromised.

As I said many times, we want to live with Russia but not inside Russia. This brings us to so-called “new Russia” or “Putin’s Russia” and her “negative conditionality” pattern that Russia offers to all her neighbors : either with us or against us. I talked about that above. We all know that the South Caucasus region’s conflicts were stirred and exacerbated by the Kremlin right after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, however the plans to instigate and provoke them were ready long before the USSR collapsed – different versions of those divergences – one for Ukraine, another one for the South Caucasus and specifically Georgia and so forth.

And nowadays, as I stated, we witness how Russia attempts its old imperial adventures following, as admitted by Professor MacFarlane, a 19th century logic in a completely different world and circumstances. Russia succeeded her brutal aspirations in Georgia in 2008, dismembering it ruthlessly but afterwards became embroiled first in the Second Karabakh war and now in Ukraine. So, especially Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has shifted the global geopolitical situation in ways that have eroded Russia’s power and influence, and thus damaged her strategic interests that any country, big or small, in the world has. Tom Graham admitted that eloquently: “The Euro-Atlantic community is more unified than it has been in decades. NATO has rediscovered its original mission of containing Russia. If we turn to so-called “Global South” where Russia wanted if not to dominate but to be one of the principal handlers, the reality is that both China and the United States remain much more active in that region, and much more influential than Russia, but specifically the countries of the “Global South” do not want to get caught between Russia and the United States, or more accurately between China and the United States. They may not have followed the Western sanctions, but neither have they delivered to Moscow much substantive support.” In short, Russia’s aggression has led, as I said above, to a deterioration of global standing and complicated the geopolitical challenges she faces. But the real problems Russia – and maybe the West – encounters are in the post-Soviet space. Everybody desires stable and secure Russia, a ”cooperative Russia”, as the West needs, as some say, “situationally” Russia’s capacity to deal with different kind of non-traditional, or asymmetric threats and challenges such as the arms control, disarmament, climate change, international terrorism and so forth.

We, in Georgia, understand that here’s a strategic trap: The West would never have that kind of “cooperative Russia” unless Russia herself does not settle her relations with her post-Soviet neighbors and admits that that these entities are now sovereign and independent states. With their own strategic agendas and goals and any attempt to reconstruct a “Soviet” or even “Russian Empire” is just, mildly speaking, wishful thinking. Even if somehow or someway Russia succeeds in that regard, that would be a “fake success”, which would devour Russia herself and her political fabrics.

And the war with Ukraine reaffirmed that dire perspective, as, I admitted that above, we all need a stable and prosperous Russia, as democratic as possible thus cooperative Russia and maybe more than Westerners. When I say “wishful”, I mean the everlasting problems of mental maps and mental landscapes still enshrined in some Russian mindsets, including the of so-called Russian democrats and liberals. I had many chats in that regard with my Russian friends and colleagues.

Where’s Russia’s good-neighborly policy, similar to what the EU had a while ago for the post-Soviet space? I remember a big gathering in Berlin on the wider Black Sea region, sometime in 2006 when I posed the same question to my Russian colleague, a well-educated and, as we say, European minded person, as Americans loved to call, “westernized”: Where was Russia good-neighborly policy? I remember, my Russian colleague got angry and responded quite harshly to me in the presence of totally appalled participants of the conference: “Russia did not have and never would have that so-called “good- neighborly policy, Mr. Japaridze!” Wow!

Indeed, in the words Fyodor Tyutchev, a wonderful Russian poet,

“You will not grasp her with your mind or cover with a common label, for Russia is one of a kind — believe in her, if you are able…”

By the way, as we know, Fyodor Tyutchev was not only a famous poet and a diplomat but a quite an effective spy. So supposedly, I would have two questions to Fyodor Tyutchev was he alive today: How to believe (верить) in Russia, what would be propositions for that, especially after the events in Ukraine but also not forgetting Georgia of 2008 as well? And why everybody (almost everybody) in Russia’s neighborhood prefers to escape from Russia, prefers to join NATO or the EU to feel secure? Why do we not feel secure being in Russia’s neighborhood? I was going to craft two questions and produced three. Sorry for that! And, by the way, these are merely trivial questions and we all know the answers to them.

AK: May I ask you my favorite question: Do you consider South Caucasus a “region”, or just three countries with totally different vectors? Is there a future for substantial regional cooperation in the South Caucasian format, or in a wider Black Sea format?

TJ: I like very much your question as it brings us to the current state of affairs and perspectives of the South Caucasus. As I noted above, the Second Karabakh War dramatically changed it strategic landscape, balances of power there, opened some perspectives for new trade and commercial interactions but still, as I feel and even see, there’s one missing element in that strategic evolving new regional image or paradigm: politicians, scholars, experts still speak about the South Caucasus not as a whole region but an area composed of three separate states with their own historical and cultural legacies, strategic agendas and goals. To make my point short and precise: There’s no regional connectivity in the South Caucasus as it is in Scandinavia, the Baltic area, and maybe even (in certain ways) among Central Asian states.

To make my point short and precise: there’s no regional connectivity in the South Caucasus as it is in Scandinavia, the Baltic area, and maybe even (in certain ways) among Central Asian states.

Recently I read and profusely enjoyed Laurence Broers’ (UK Conciliation Resources and Chatham House) observation on the connectivity issue, which was published by the way, by your Caucasian Journal. As Mr. Broers acknowledges, that “connectivity embraces not only access and transit, but also the nature and density of other kinds of connection: the civic ties, transnational networks, everyday interactions and communities of practice that embody a networked connectivity between and among societies and social spaces.”

Indeed, the South Caucasus connectivity capacity is currently focused on a “thin”, as defined by Mr. Broers, conception of connectivity focused on large, state-directed infrastructural projects, rather than a “thicker” conception of connectivity encompassing actors and spaces beyond the state. I have been thinking about that quite long time and I talked about those delicate and complex issues for years with my friends, including from Azerbaijan and Armenia. The question that instantly comes to my mind is whether the Second Karabakh War, which reconfigured the entire landscape of the South Caucasus, opened doors for that kind of quiet conversations without TV cameras and press and specifically among some knowledgeable, intelligent, experienced enough, let’s call them “regional wise men”, on those “elements of “thicker connectivity”? Has the time come for that?

Watching the ongoing South Caucasian discourse unfold, I comprehend that politicians, academic circles, experts still, if not ignoring, but somehow are cautiously reluctant to observe the South Caucasus as a region. What’s the motive for that neglect? Maybe it’s still too early as the aftershocks of the Second Karabakh War are still excruciating. I posed the same question to Professor MacFarlane, a long-time expert on the thorny South Caucasian issues, and he responded that “the passivity is based on the fact that our region encompasses geographical contiguity or proximity.”

I would agree with Professor MacFarlane’s judgment, but that’s not enough to fully understand the problem. I traveled enough throughout the South Caucasus and I detected that we – Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Georgians – do not know each other’s history, culture, particularly our shared cultural features and connectivity, our centuries–old lack of engagement (instigated and intentionally promoted by our former Imperial patrons) with neighbors and thus the lack understanding regarding the closeness of traditions and cultures. I have been focused on the problems of South Caucasus for years but do we know well the history and cultural legacies of the Black Sea littoral states? Do Georgians know the traditions, habits, legacies of Turks, Bulgarians, Romanians? For some years I was the Secretary-General of the BSEC (Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation) , the only regional international organization supposed to promote trade, commerce and thus connectivity among the littoral states but not only. However, I witnessed myself those futile battles among the member-states over some insignificant things and problems that distracted relationships and connections.

AK: Foreign investments are critically important for Georgia, and you have been directly involved in one of the main projects – Anaklia Port. Though Anaklia (preceded by Lazika) hardly can be considered as success so far, we hope this important project will move ahead, and followed by many others. But when? The deadline for investors to submit proposals expired on June 19. Can you comment on Anaklia project situation, or generally on the situation with FDI?

TJ: Georgia could have indeed rapidly become a global trade and transport center, a juncture from Europe to Asia and vice versa, had we empowered our new deep-water port in Anaklia. We expected that the Anaklia Sea port could have accelerated foreign direct investment flows and Georgia’s central position in the eastern shores of the Black Sea. Georgia is where West meets East and North meets South.

Due to the war between Ukraine and Russia, all Russian seaports are under sanctions and almost all Ukrainian seaports are either demolished or damaged. We can only imagine where Georgia could have been trade and commerce-wise on a global scale had the Anaklia deep-sea port been operational.

We have been dedicated for years to making Georgia a compelling gateway for trade and commerce to the world, empowered by a stable democracy and a vibrant free market. In general, the South Caucasus remains one of the most perplexing regions of Europe. The countries of the area—Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan—were often isolated by culture and history and we talked about that above. But on the other hand, the South Caucasus, and specifically Georgia, with an access to the Black Sea infrastructural capacity and with that supposed to be build a new deep-water port in Anaklia, could have transformed itself into a “leap region”—a regulatory and infrastructural bridge leaping across Europe and Asia. The goal was to make Georgia a modern hub for both continents. In particular, the new deep-sea port could have formed the core of Georgia’s version of so-called “localization”. Located at the crossroads of geopolitically significant trans-Eurasian trade corridors, Georgia could have realized its geopolitical potential by combining infrastructure developments such as the Anaklia port with growing regional supply chains. So, earlier to localize this global potential, Georgia has partnered with Azerbaijan and Turkey in the development of energy projects, later the Baku–Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway network, whichin conjunction with Kazakhstan’s Khorgos dry port – shortens the voyage from Europe to China to fifteen days; that’s twice as fast as shipping. Georgia’s coastline on the Black Sea is the only route, as admitted above, from Europe to China that doesn’t run through Russia. That was significant for Ukraine, which in 2015 replaced even the United States as the biggest exporter of corn to China and is also the eighth producer of soybeans in the world. Of equal significance is the need of major European food exporters to reach the Central Asian hinterland, China, and the Middle East. The Middle Corridor from Georgia to China could have become the market driven by players who are motivated to modernize regulation and infrastructure to reduce transport costs.

As you may noticed I have used many “past perfect forms” for my answers as the Anaklia project that could have raised Georgia on different strategic level had been congested due to some political, personal or bureaucratic debris. And more than that the case now in arbitration and we do not know yet what would be the conclusion of that settlement. The Government talks about some new tenders but I have not heard anything specific in that regard. Meanwhile, as I said, due to the war between Ukraine and Russia, all Russian sea-ports are under sanctions and almost all Ukrainian sea-ports are either demolished or severely damaged. We can only imagine where Georgia could have been trade and commercial-wise on a global scale had the Anaklia deep-sea port been operational.

AK: Is it true that the foreign investors’ attitude to Georgia has changed? In your view, what is to be done to attract serious international investors to this country?

TJ: My answer would be short and straight-forward: Georgia should accomplish a full-scale judiciary reform and cement the rule of law in our everyday life, strengthen our belief into our court-system. If that happens then we shall witness the flow of serious FDI and visits of solid international investors. Currently the flow of FDI is weak and insignificant in courtiers where the judiciary system is problematic and courts are biased. The foreign investors prefer to avoid this kind of problematic countries.

AK: We do not often have a chance to interview speakers of your caliber. I wish we could hear more from the nation’s most experienced people – otherwise the fake experts and fake ideas may take the lead. Would you like to comment on this? How can a society be stimulated to listen to the smart and experienced?

TJ: I do not know how to answer your question as I feel that our society itself happens to be more or less comfortable with that kind of sham veracity I would say, that there’s strongly demand reality. Those people expect daily portion negative, neurotic news and when they get their regular dose,they feel thrilled, morphed enough . So, we swallow different versions of developments and their interpretations of what happened in our own country but according to the political taste or skills of different news-makers/influencers or news interpreters, or would better to say, different news-manipulators and their political patrons! By the way, that maybe “today’s news” cooked yesterday in some smoke-filled rooms. And in the end, watching that news diatribe, we stay in total confusion as if watching developments in different countries and not in our own one. Very regrettable reality! But it’s not only a Georgian pastime! It’s become a global commodity, and it is indeed nasty and horrible one. I very much regret to acknowledge that and I wish to be wrong!

Georgia should accomplish a full-scale judiciary reform and cement the rule of law in our everyday life, strengthen our belief into our courts system. If that happens then we’ll witness the flow of FDI and serious international investors.

AK: If there is anything that you would like to add for our readers, the floor is yours.

TJ: Just want to thank you very much for your patience to listen my long conversation, even excruciating tirades and elaborations! I have tried to share with you and those who may read that interview only my personal and sincere views, being focused, by the way, specifically on those mistakes and blunders, committed by myself and my generation of decision-makers. So, I may be wrong in my assessments and analyses. Some mistakes or blunders I described were unintentional and due to our inexperience and simple naïveté. However, there were also several intentional bloopers, mistakes, zigzags and crisscrosses, deviations, and even, as I admitted, betrayals. That’s how Georgia moved ahead and has been doing that nowadays. Some things could have been done in much better and resolute ways, but we still have accomplished many things and we need to learn how to preserve that unique legacy of accomplishments but also of mistakes made by our predecessors and not to demolish that national treasury – the experience and the knowledge – being obsessed with mania of reinventing the wheel. Yes, again, we are not perfect but who’s perfect in today’s world? All of us love, admire Georgia, our country that belongs to everybody whether you are in the majority or in the opposition – it belongs to the citizens of Georgia. With the same way and with same vigor we need to take care of the State and make it stronger but also as democratic and capable as possible. That’s kind of truism that only a strong State, based on the rule of law and strong viable institutions, would have the capacity to defend Georgia, a country, which we all so much revere!

AK: Thank you very much!

TJ: There’s yet much to talk and observe, and share that experience, including bad one, with the next generation of Georgians not to keep them forever running around that vicious circle of mistakes, blunders and naivety. The world is going, as admitted by Chancellor Olaf Scholz, through a “Zeitenwende period” [turning point] and so, each country needs to make its foreign and security policy rethink, which usually should be based on sound and well-balanced, democratic domestic strategy. I hope that Georgia will do that properly – realistically and pragmatically.