By Corneliu Pivariu

The leaders of BRIC[1] (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) first met in St. Petersburg, Russia, during the G8 Summit in July 2006. This was followed by a series of high-level meetings, after which the first BRIC summit took place on June 16, 2009, in Yekaterinburg, Russia. After the inclusion of South Africa in 2010, the group was renamed BRICS.

Before this year’s summit, the group represented[2] 41% of the world’s population (3.14 billion people), 24% of global GDP, over 16% of world trade, and 29.3% of the total land area.

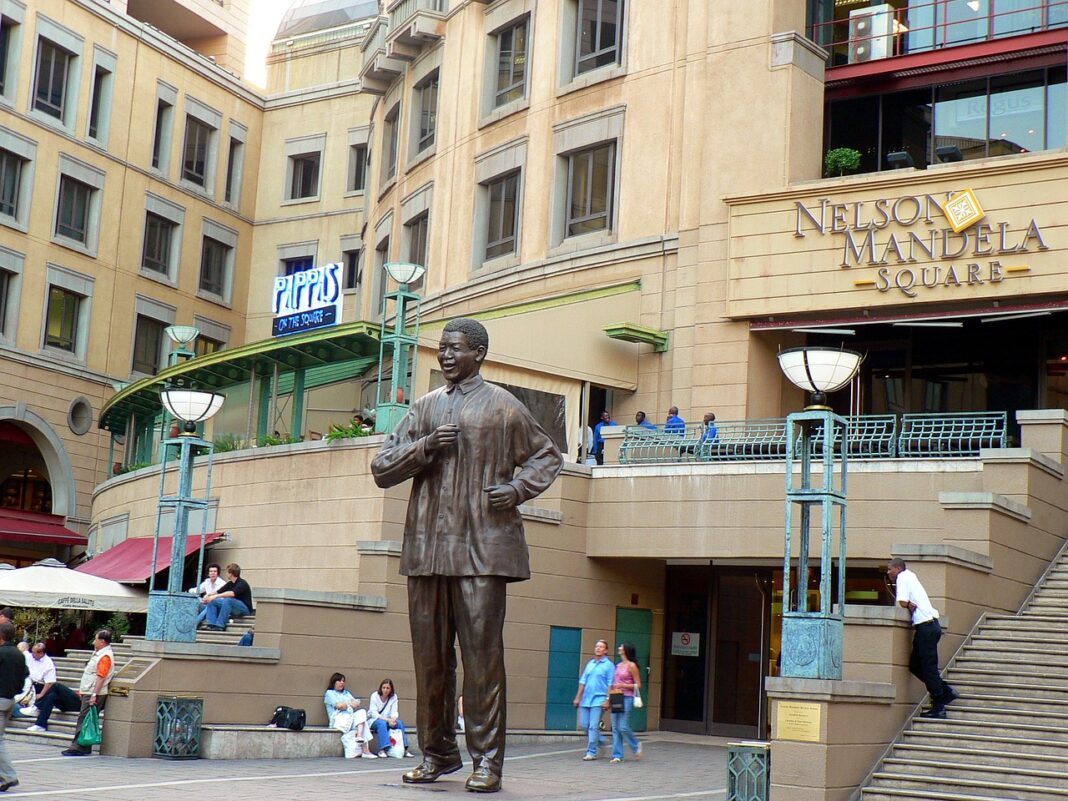

For the BRICS Summit held in Johannesburg, South Africa, from August 22-24, 2023, invitations were extended to leaders from 67 other countries, resulting in over 500 official participants at the event. Notable for the summit were the physical absence of Russian President Vladimir Putin, due to an arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the first part of 2023, and the absence of a speech by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who was represented by China’s Minister of Commerce. The reasons for President Xi’s decision were not publicly disclosed.

The main points on the summit agenda included:

- Expansion of the BRICS bloc, as over 40 nations expressed interest in joining, with 23 having already submitted official applications.

- Economic cooperation among Global South states in areas such as investments, energy, strategic infrastructure, and innovative technologies.

- Prospects for developing common monetary and banking relationships.

- Global security issues, including matters related to new structures of international order.

It’s noteworthy that while this last point was discussed during working sessions, none of the BRICS leaders addressed it in the conclusions following the presentation of the final declaration, “Johannesburg II,” which was presented by the host country’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa. Additionally, there was no mention of the bilateral understanding reached in Johannesburg between President Xi and Prime Minister Modi regarding mutual de-escalation of border tensions between China and India.

The expansion of BRICS was realized through the consensus decision to admit five new members from January 1, 2024: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This marks the first expansion in 13 years, with BRICS leaders stating that the door remains open for new members, considering that 16 more states have officially applied for membership, and about 20 countries have expressed unofficial interest in joining the organization.

It’s worth emphasizing that in the final evaluations of the delegates at the summit, President Xi Jinping listed the newly invited states to the bloc, starting with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. These states are part of BRICS+, a group that will have the potential to produce over 50% of global oil. Furthermore, the combined GDP of the BRICS+ states will exceed 37% of the total nominal global GDP (surpassing the combined GDPs of the G7 countries), and their share in global trade will be over 20%. Notably, the combined population of the BRICS+ countries surpasses 46% of the world’s total population.

The prospects for numerical growth of the group will make it a powerful entity in international political negotiations in the near future. However, it’s important to recognize that there are Western political leaders and analysts who continue to downplay the significance of BRICS, including BRICS+, considering it “largely a dysfunctional organization that cannot gain weight through mere expansion. At the core of BRICS are three immature democracies – South Africa, India, and Brazil – who want to maintain a constructive relationship with Western financiers, while at the extremities are China and Russia as autocracies.” Nevertheless, the final summit declaration, presented by South African President Ramaphosa, indicated that BRICS has followed a strategic course with a clear perspective, responding to the aspirations of a significant part of the international community, acting in coordination based on principles of equality among states, mutually supporting each other as partners, and considering the interests of others in addressing urgent global and regional issues. When addressing security matters, Ramaphosa emphasized the need to respect the provisions of the UN Charter for dispute resolution through dialogue.

Argentina joining BRICS after Brazil means two giant countries. The inclusion of Ethiopia[3] might seem surprising, but it’s symbolic and a magnet for Sub-Saharan and Central Africa. Moreover, China has strong relations with Addis Ababa, and South Africa wishes to emphasize Africa’s importance.

Symbol and substance, two words that can apply to describe the expansion. G7 is big, AUKUS is big, NATO is big. BRICS+ must be big, global, and resourceful.

Regarding the process of “de-dollarization” and the creation of a specific BRICS+ currency, it is believed that this is far from materializing into an alternative currency that would challenge the supremacy of the American dollar in the foreseeable future.

Dilma Rousseff, President of the New Development Bank[4] (NDB) of BRICS+, presented a written report on the institution’s goals. The NDB intends to provide loans in national currencies, especially in South Africa and Brazil, as part of a plan to reduce global dependencies on dollar settlements and promote a multipolar international financial system. This approach aims to avoid risks posed by the dollar-based exchange rate and fluctuations in US interest rates. In the initial phase, the NDB plans to provide loans of up to $10 billion by December 2023. The medium-term goal of the NDB is to have 30% of all loans within BRICS+ be in national currencies, and importantly, without any political preconditions (unlike the IMF and World Bank’s practices).

This idea, presented in Johannesburg, poses the most impactful challenge to the Western community and represents a strategic risk in the long term for the entire Western world. The implications of the possible success of this initiative could disrupt the stability of the entire global military and socio-economic security system. This idea is explicitly mentioned in point 10 of the final Johannesburg II communiqué: “We support a robust global financial safety net with an International Monetary Fund[5] (IMF) based on quotas[6] and with adequate resources. We call for the conclusion of the 16th General Review of Quotas of the International Monetary Fund before 15 December 2023. The review should realign quotas in the IMF. Any adjustments to quota levels should result in quota increases for emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), protecting voice and representation for the poorest members. We call for the reform of the institutions of the Bretton Woods Agreement[7], including a greater role for emerging markets and developing countries, including leadership positions in institutions of the Bretton Woods Agreement that reflect the role of EMDEs in the global economy.”

Another conclusion to draw from the Johannesburg summit is that the BRICS+ group is starting to intensify its challenge to the US’s position as the world’s number one power by countering the West’s use of sanctions against Russia and, more importantly, by attempting to weaken the role of the dollar as the reference currency in international transactions, as well as shaping a new policy in the global energy industry (oil, gas, and nuclear energy). The perspective does not appear positive when considering the efforts of Venezuela, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, and Cuba to get closer to BRICS+. These countries are accelerating the trend of restructuring the current global order toward a multicentric one, without a dominant actor from a geopolitical and economic perspective, even though they strive to refrain from developing explicitly anti-American rhetoric.

Another emerging perspective after August 24, 2023, is that the West (probably with the exception of Germany) can no longer afford to ignore BRICS+ as an entity. In this context, the US will need to rethink its foreign policy regarding the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific region, as well as the future of bilateral cooperation with Algeria, Egypt, Brazil, South Africa, and India, especially in terms of continuing arrangements in the QUAD (India, Australia, Japan, USA).

Finally, a rhetorical question arises. Does the recent BRICS summit in Johannesburg signify the beginning of a project lacking transparency (i.e., undemocratic) subtly hinted at by two famous phrases that the world continues to decipher?

First: “Cooperation between Russia and China will be limitless.” (from the official statement after Vladimir Putin’s visit to Beijing, February 2022)

Second: “We are now witnessing changes that haven’t been seen in over a century, and we are experiencing them together. Take care, dear friend!” (Xi addressing Putin through an interpreter as they bid farewell in front of the Kremlin during Xi Jinping’s state visit to Russia, March 2023)

The Johannesburg summit might also represent a real opportunity for Washington to reset its entire foreign policy framework focused on BRICS+ due to the likelihood of a new wave of countries being accepted into the core of the Global South in the near future. Many of the developments in global stability will depend on the actual growth rates of China, India, and the Russian Federation, which are not without uncertainties, as well as how the US will overcome obstacles arising from the diminishing status of its hegemonic role.

At the same time, the internal limitations and difficulties of BRICS+ must not be overlooked, along with the differing interests among its members and how they will work toward achieving common goals.

“Interesting times” lie ahead!

The text is a presentation by General (Rtd) Corneliu Pivariu at the international webinar “To BRICS or not to BRICS – that is the question,” organized by MEPEI and EURODEFENSE Romania, on August 30, 2023.

About the author:

Corneliu Pivariu is a highly decorated two-star general of the Romanian army (Rtd). He has founded and led one of the most influential magazines on geopolitics and international relations in Eastern Europe, the bilingual journal Geostrategic Pulse, for two decades. General Pivariu is a Military Intelligence and International Relations Senior Expert.

[1] The acronym BRIC was first used in 2001 by economist Jim O’Neill from Goldman Sachs, who described what he considered to be the countries with rapid economic growth that he believed would dominate the global economy by 2050.

[2] World Bank data from 2019.

[3][3] Ethiopia covers 1,112,000 square kilometers and has a population of 120.5 million (ranking 13th globally and second in Africa). It possesses natural resources such as gold, phosphates, natural gas, copper, platinum, graphite, lithium, precious stones, and tantalum (a crucial raw material for electronic components). Ethiopia maintains excellent foreign relations with China, Israel, Mexico, Turkey, and India.

[4] Established in 2015, headquartered in Shanghai, China. In 2019, it opened its branch in Sao Paulo, Brazil, followed by branches in India and Russia. Subscribed capital is $50 billion, initially authorized at $100 billion.

[5] IMF monitors exchange rates and manages countries in need of financial support. World Bank manages the assistance funds required by countries facing financial difficulties.

[6] National quotas are expressed as a percentage of total SDRs (Special Drawing Rights) and determine each nation’s voting power at the IMF. For instance, China holds 9,525.9 SDRs or 4%, Russia 5,945 SDRs or 2.5%, and the US 42,122.4 SDRs or 17.69%.

[7] The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944) – signed by representatives of 44 allied nations, who decided that gold should constitute the reference standard for establishing a fixed exchange rate. Subsequent developments led to the replacement of gold with the US dollar, enabling the US to become the regulator of global trade through the Federal Reserve. The agreement facilitated the creation of significant financial structures: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), now known as the World Bank.