By Richard T. Griffiths

Whilst teaching a summer course at Ocean University, Qingdao, I took a road-trip with my archaeologist colleague, Sarah Ward, to Nanjing to see for ourselves the city portrayed in the first site in the Silk Road Virtual Museum.

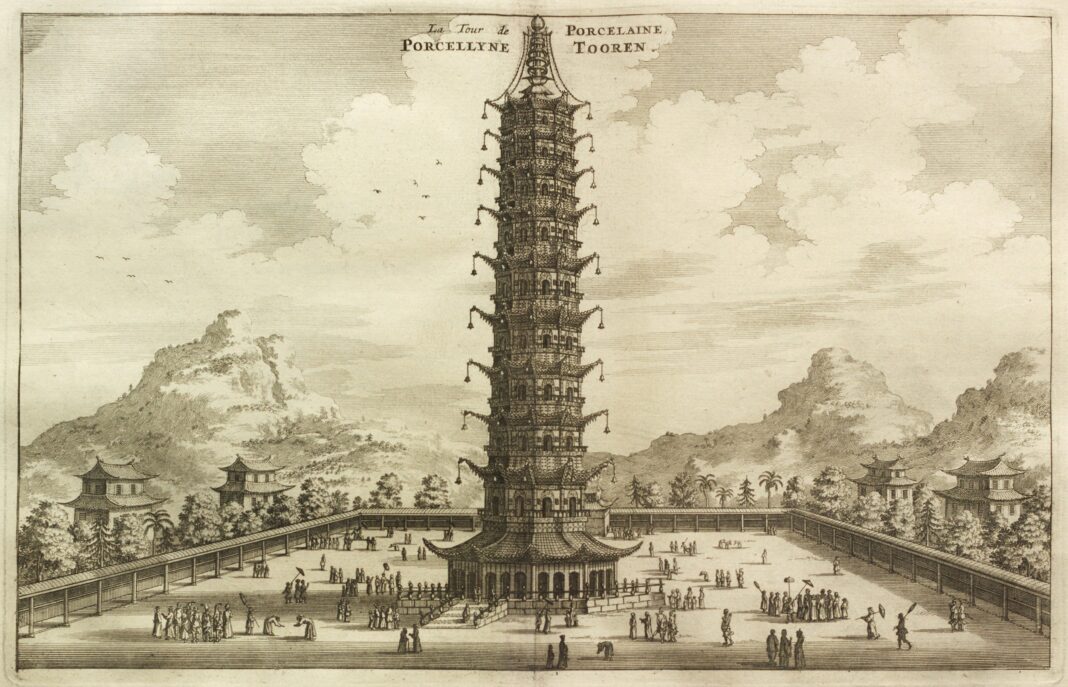

Nanjing was famous for its Porcelain Tower, described as one of the wonders of the medieval world, commissioned by the Yongle Emperor (1402-1424 CE) to honour his mother and eventually destroyed during the Taiping rebellion in 1856. We had heard mixed reactions to the rebuilt tower and the museum surrounding it, so decided to see for ourselves.

The site of the tower was on the south banks of the Qinhai River, just beyond the city walls. There had been a Buddhist temple on or near the site continuously since the third century CE and, since the eleventh century CE the temple had boasted a nine-storey pagoda/tower. In 1406, however, the tower was destroyed by fire and six years later, the Yongle Emperor ordered the construction of its replacement on the site, also known as Bao’ensi (meaning “Temple of Gratitude”).

It took 100,000 labourers seventeen years to complete the entire project. The Yongle Emperor died before its completion. The octagonal tower was almost 80 metres high and constructed of white porcelain bricks and decorated with colourful Buddhist tiles. The tower shimmered in the sunlight and, at night, the oil laps, hanging from the eves, twinkled in the dark. By all accounts, it was sensational. In 1665 readers in the West were able to see the building for the first time.

Entrance to the Museum

The rebuilt tower is still an imposing structure as you approach it from the road. We were pleased to see that although the structure of the tower remained faithful to the original, no attempt had been made to imitate the exterior decoration. The exterior netting allowed it to glow in the evening sun, as we viewed it during a short river ‘cruise’ and I was quietly pleased we left before the ‘light show’.

There was a short queue to enter the museum and it was interesting to see that some people still ‘dress-up’ for a museum/temple visit, though evidently there was no consensus on what constituted an appropriate style.

‘No agreement on appropriate style’

Once inside, passing by the water course and bridge, it was clear that we were in an archaeological site. The one remaining stele made clear the difference between the original and reconstructed elements, and no attempt had been made to replicate the missing stele on the opposite side of the complex. All the uncovered surfaces over what had been temple halls were left in situ, and glass passage ways allowed visitors unencumbered access to all the exposed public areas.

Every effort was made to avoid compromising the original, to the extent that, when providing visitors the impression of a colonnaded hallway, the columns were hung from the roof to avoid them touching the floor. Sarah was fulsome in her appreciation – fully consistent with best archaeological practice.

The colonnaded hallway

The contextualisation of the site was also excellently done with explanatory panels (also in English) maquettes, models, and multi-media presentations. The problem came with the historical artefacts on display. Let’s take the example of the entry portal to the original tower, beautiful and large as life.

Entry Portal to the Porcelain Tower

The problem with this is that there is an identical one in the Nanjing Municipal Museum. Which one is real? Judging by the state of the tiles on display, actually recovered from the site, probably neither. But once doubt is fostered over the providence of one artifact, doubt begins to spread. Knock on the side of the impressive ‘jade’ fountains and you discover that they are made of resin – OK, no signs says they are actually jade, but what are they doing there? We are looking at some Ming porcelain on display, with no explanation as to why it should be there, when a visitor walks past and murmurs ‘all fakes’ in a loud voice and gives us a huge wink.

The next part of the museum was devoted to Buddhism. I am not a Buddhist and what I write in the paragraph is not intended to be offensive. I am simply telling what we saw. The panels explaining the main elements in the religion and their symbolism is accurate and reflective, and the bronze and gold statues are well presented. In the next room there are several white, oversized, seated and reclining Buddha statues, alternately lit in blue and white gaudy lighting that reflects off the mirrored walls. To reach the ‘partner’ room of the other side, you walk through a brightly lit tunnel with ‘silk road’ type scenes and pastel ceiling, evidently catering for children.

A winter wonderland paradise

And it is the children who can offer the only plausible explanation of what came next – winter wonderland paradise with mother-and-babe statues nested in the rolling countryside, unthreatening and at peace, while a computer graphic changing universe is projected on the back wall. The final stage in the trail of Buddhist representation comes underneath the tower itself. There, in an impressive octagonal space is a gigantic lotus-leaf cupola, protecting a golden shrine. Below, several people are in deep contemplation or prayer. Real or not, it offers peace and solace to some seeking it.

The lotus canopied room

It is difficult to know what to make of the museum. The state of archaeological preservation is first class and the historical context is well and imaginatively presented. I could even accept the use of replicas, if only they were clearly presented as such. The second part of the museum was clearly not designed for me. If people get understanding or pleasure from it, it evidently serves its purpose for them. And the tower itself – magnificent. Our last memory was observing it from the river, basking in the evening sunset.

A final view. In the evening sunset

The Porcelain Tower is featured in the Virtual Museum. I will be replacing the existing video with one of my own.

You can see everything at https://silkroadvirtualmuseum.com