By H.E. Mr. Suljuk Mustansar Tarar, Ambassador of Pakistan

An exhibition on art and life of Frida Kahlo held at Drents Museum, Assen in the Netherlands took me back to Lahore, my home town. I had seen Frida’s work in New York and Diego Rivera’s murals in Detroit where Frida accompanied him but the exhibition at Drents introduced me to Frida’s multiple personas and more importantly as a human trying to keep her head high amidst her collapsing physical edifice. It showed Frida’s zest for life, creativity, attention to design details for dresses, corsets, and shoes, a carefully built persona, symbols of self-love and losses, frustrations, and global connections in the early half of twentieth century, love for men and women, breaking every day norms, and touching boundaries, which even today are unthinkable among many others.

Curated by Drents Director Harry Tupan, the exhibition had Frida’s paintings, dresses, books like the Walt Whitman’s anthology that was on Frida’s side table when she died, letters, cosmetics, shoes, medicine bottles and rare photographs. On how was Viva la Frida a different exhibition from others organized Tupan said that “The exhibition Viva la Frida – Life and art of Frida Kahlo was an overall concept as we were able to showcase not only her famous artworks but also her personal belongings. The paintings, drawings and photographs along with her clothes, jewelry and medical supplies gave a layered picture of the iconic woman Kahlo was in terms of art, inclusivity, gender and politics”

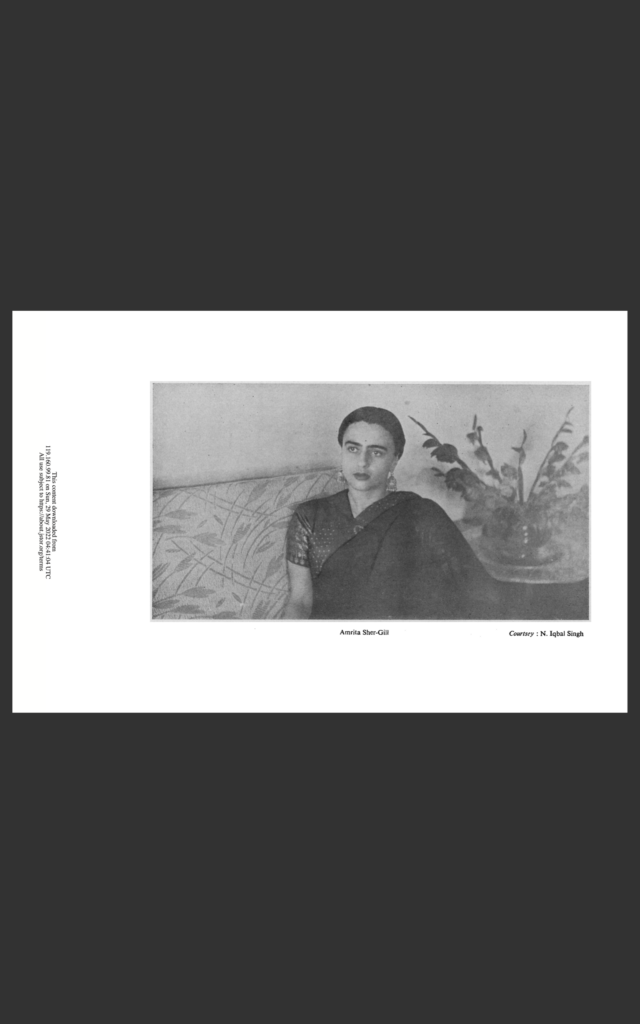

As I moved in Drents through a joyous and colorful exhibition celebrating Frida’s life and works she became real and there she reminded me of Amrita Shergil – the pre-independence bohemian artist who spent her last months in Lahore, the city which opened doors to Amrita when rest of the sub-continent seemed not to be working in her favor. Amrita is at times compared with Kahlo but the more I discovered the two great women artists of early twentieth century, the more they appeared like two identical twins who had existed in two different corners of the world.

Growing up in a historic city like Lahore has its unique advantages. One is able to follow steps and stories of people who once lived and breathed there. In the Raj era and for a long time after independence, the Mall Road of Lahore was a hub of art, academic and literary activities. Amrita Shergil lived just off the Mall Road in 23 Ganga Ram Mansion one of the dozen red brick proto-type designed colonial banglows.

Despite the passage of significant time the place still breaths of colonial era. When I last visited the place in June 2022, it felt that Amrita was still upstairs in her studio finishing her last painting. Her studio was in a room, commonly known as rain storage unit – barsaati, on top floor of Banglow no 23. Kahlo spent much of her life in Casa Azul (the Blue House) in Mexico City built by her father Guillermo Kahlo, a German, who had moved to Mexico from Hungary after the death of his first wife in childbirth and married a Mexican indigenous woman Matilde Calderon.

Amrita was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1913 to a Hungarian mother and an aristocratic Sikh father and died young at the age of 28 years. Frida Kahlo was born a few years earlier in 1907 in Mexico City and both had a mixed parentage. Though Frida outlived Amrita by two decades yet she too was young to die a few days after turning 47. She left behind 200 paintings and sketches including 55 self-portraits, kept a diary with details and sketches giving a window to her life. Amrita’s known works are around 143 and her early focus was on nudes which as expected created ripples. She also did self-portraits. Her work mostly remained figurative. She regularly wrote letters and articles explaining her work, which means that as an artist she knew the importance to explain her work like Frida did through her diaries and consciously built image.

Frida was stricken by Polio at the age of six and met a devastating accident at 18 when a bus she was travelling in was hit by a metro-tram. Despite her disabilities, her immense love to draw could be seen in one of the photos at the Drents exhibition where she is lying on a bed with easel and a specially placed mirror on the roof allows her to see and draw. She married a much older and much accomplished Mexican artist of the time Diego Rivera. Their relationship remained fluid but friendly. Frida Kahlo’s persona is a key part of Mexican cultural and soft power and the Mexican Ambassador in Netherlands Jose Antonio Zabalgoita also utilizes this icon said that “Frida Kahlo is the best-known Mexican artist. Her works, her ideas and her rebellious personality certainly anticipated current principles and values for women’s rights. As Ambassador of Mexico, I rely on Kahlo’s powerful figure to underscore Mexico’s cultural identity.”

Amrita’s father Sardar Umrao Singh Majithia was a scholarly man with interest in philosophy, religion and photography. Frida’s father also indulged in photography. Amrita’s mother Marie Antionette was a musician and an opera singer. She came to India with Princess Bamba Singh, the grand-daughter of Mahraja Ranjit Singh, and a resident of Lahore’s Model Town. The Sardar married Marie-Antionete an esoteric woman after the death of his first wife.

Sardar Umrao Singh Majithia decided to move back to subcontinent after the First World War in 1921 where Amrita found early on her love for painting. She was tutored by Hal Bevan-Petman (1894-1980) a British portrait expert who stayed on in Pakistan after independence and became an important elite portrait maker in the early years of Pakistan. Shergil left India for Paris from 1929 to 1934 to study at Ecole des Beaux. At the Paris Grand Salon her painting “Young Girls” got an award. Amrita had the honor of becoming an Associate of the Salon at the age of 18. She was also exposed to the works of impressionists and became an admirer of Paul Gaugin. The influence can be seen in her different works especially her 1934 self-portrait. “Some have even suggested that she approached India as a foreigner, motivated by the same spirit of exotic discovery as was Gauguin in Tahiti.”[1] She is also at times termed as post-impressionist and considered one of the first modern painters of sub-continent.

Frida used Aztec mythology and later used Hindu mythology in her work which showed that she was in some way exposed to the subcontinent. Frida’s work is full of symbolism from her roots, her life and travels e.g. to the US. Amrita as she stayed in subcontinent was able to identify with her father’s land. Her work shows melancholic and lonely subcontinental female characters.

Kahlo was termed a surrealist but Kahlo said that she painted her own reality and did not paint dreams. Her work does seem surreal with strange stories of a woman lying in blood, animals hovering around and dream like images. The Two Frida’s and The Wounded Table were displayed at an early exhibition in Mexico on surrealism. Frida was a life-long communist and a revolutionary but led a life of privilege with Diego Garcia. Amrita’s artistic concerns or empathy for natives can also be seen from her lens of privileged life she spent. Amrita was an elitist prodigy but did struggle towards the end of her life having married her Hungarian cousin Dr. Victor Egan who could not run a successful medical practice and ended up in a small town of Suraya where Amrita’s family owned a sugar mill. That time was a period of creative dryness and marital troubles for Amrita. Both decided to move to Lahore in September 1941.

Amrita held her first single-person exhibition in Lahore in November 1937. The exhibition showed 33 works by Amrita and was organized by Dr. Charles Fabri an Hungarian Indologist and leading art-critic of the time working for the famous paper Lahore Civil and Military Gazette. It was also during this visit Amrita saw Lahore Museum and its miniature collection, and visited Harappa. Lahore was the cultural hub of sub-continent and this exposure to the life in Lahore probably led to the decision by Dr and Mrs. Egan (Amrita) to move there in September 1941 thinking that it would result in a better career move for both.

Frida held her first major show in 1938 in Julien Levy Gallery New York. Frida desperately wanted to be a mother but could not carry a child because of her medical problems. She had had miscarriages and abortions – the unfulfilled desire to be a mother is seen across Frida Kahlo’s different works like the Henry Ford Hospital (1932). Kahlo died of pulmonary embolism though some suspected of suicide. Shergil, on the other side, seemed to avoid motherhood and an abortion might have caused her early death only after two months of arriving in Lahore and looking for a breakthrough.

Frida became known to the world in early 1980’s with increased interest in feminism and decolonization and more so in this century. Amrita remained known to the subcontinent art circles but got much more attention towards the end of last century and in this century. With their mixed heritage and international exposure of the time both Amrita Shergil and Frida Kahlo invoked their “otherness” through their work and persona and “brand their otherness….in universally recognizable terms.”[2] Kahlo wore the Mexican Tehuana and Shergil adopted the Sari as the South Asian dress. Tehuana’s colorfulness is part of Kahlo’s paintings and global image. Shergil can be seen wearing Sari in her photos and her paintings show Sari clad voiceless women. Most of all after their death Frida and Amrita have been re-explored and reinterpreted by the art world.

About the author:

Suljuk Mustansar Tarar is Pakistan’s Ambassador to the Netherlands. He also writes about contemporary art and culture. He is author of All That Art – a book on Pakistani contemporary art & architecture published by Sangemeel Publications, Pakistan. He can be followed on Twitter @suljuk & Instagram @suljuktarar

[1] TILLOTSON, G. H. R. (1997). A Painter of Concern: Critical Writings on Amrita Sher-Gil. India International Centre Quarterly, 24(4), 57–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23002294

[2] Winther-Tamaki, B. (2014). Six Episodes of Convergence Between Indian, Japanese, and Mexican Art from the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present. Review of Japanese Culture and Society, 26, 13–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43945789