By Richard T. Griffiths

The Dragon Boat Festival is traditionally held on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month of the Chinese year. For some reason, nine hundred years ago Emperor Huizong chose to sponsor one on Jinming Lake (near the Northern Song capital Kaifeng) on the third day of the third month. The occasion was recorded for posterity by the renowned artist Wang Zhenpeng for Emperor Renzong in 1310CE. Twelve years later, he copied the painting for the emperor’s sister.

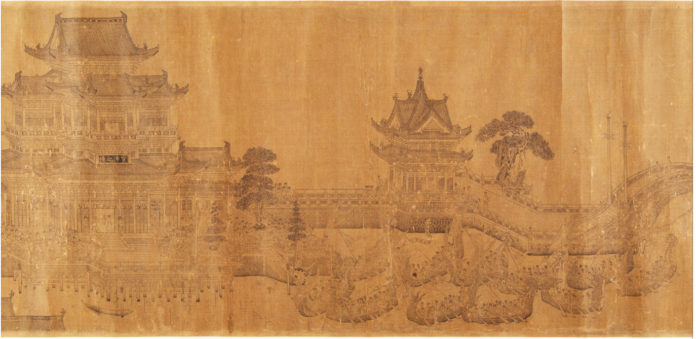

The version shown here is also probably a copy/forgery. It is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and it will feature as an animated handscroll in the Silk Road Virtual Museum later this year. The image, which shows only part of the festival, has been enhanced for your viewing pleasure (or, more accurately to allow you to see anything at all).

There are several explanations for the origins of the festival. The most obvious, for those who believe that numbers can be more, or less, propitious is that ‘five’ is considered unlucky and a double five, therefore, more so. However, that only explains the date of the festivities, not the form at they take. The most common legend is that citizens took to the boats and thrashed the water with their oars to stop a body being eaten by the fish. Although this is the most common, there are several variants. Let us take them in chronological order.

In the first, the body is of the beautiful Wu Zixu who, in 484 BCE, was forced to commit suicide by her royal husband on the fifth day of the fifth month when she tried to warn him of a plot against him. The second candidate is the poet Qu Yaun who, in 278 BCE, committed suicide, after being captured and condemned for resisting what he considered an unwise alliance. The citizens went to find the body and, on failing that, dropped balls of sticky rice into the water to stop it being eaten (another feature of the festivities). The final candidate is the young girl Cao E who, in 143 CE, dived into the river to save her father, who had himself fallen in while supervising a dragon boat festival. Both were swept down river and the citizens took to the waters to find the bodies, which they did some five days later. Regardless of how it came about, the dragon boat festival is now a public holiday throughout China.

As chance would have it, I was in Hong Kong in mid-June for a ‘Port City’ history conference with my good friend and colleague, Sarah Ward. It offered a perfect opportunity to see, first hand, what the festivities involved and to put some sound and colour into the fourteenth century images in my possession. So it came about that in the morning of 22 June we were at Stanley Beach to watch the start of the races. The heat was already rebounding off the sand as the twenty competitors clambered into each of their boats. The steersman and the drummer remained in place, and served the same boat regardless of crew changes. The friendly dragon on the bow of the boat sported a jaunty bouquet of flowers. Then, the crew slowly rowed backwards, turned and set off towards the starting line at a slow but steady pace.

Meanwhile, in the distance, some 300 metres off-shore, the far-off waters were beginning to churn. The race had started and the boats surged forwards, their crews stabbing their blades into the water at an ever-increasing tempo. Slowly the straight line begins to break and one on the right and one in the middle establish a lead over their nearest rivals, a signal of the crowds lining the shore to start shouting in encouragement. By now the boats are approaching the finish. The drummers are pounding their drums, the blades blur through the water and a white foaming wash is punched before the boats. One final surge, a gun is fired and the boats slowly lower themselves into the gentle incoming tide. In one or two boats the oars are raised in triumph, but no one knows yet who has won. At the shore the exhausted crews disembark and make way for the next competitors. All of them are welcomed into the embrace of their supporters, some more vociferously than others. There is a winner. All the teams will have completed the 270 metre course in under ninety seconds. The margins between the leaders often wafer thin.

But look up – the new crews are starting their journey to the start and… yes, the next race is already under way. I was pleased to be a neutral. I don’t think I could have survived as my A/B/Mixed/Womens teams made their way through the day. It is good to know that the sponsors of the race, Sun Life, offer a free Personal Accident Protection Plan that not only includes coverage for severe heat stroke but also a one-off compensation for death caused by participation in Dragon Boat championship. Even as a neutral, I felt I truly had participated. I confess, we left before the races ended, the temperature climbing faster than the sun was rising and scarcely a scrap of shade to be found. Next stop, to find some triangulars portion of zongzi, sticky rice with a savoury filling[Rg1] and wrapped in bamboo leaf, much too good for the fish.

The Silk Road Virtual Museum can be found at https://silkroadvirtualmuseum.com. The museum is being developed with V21 Art Space